The ‘problem’ of depression How do we understand the condition?

SPEC CHECK

■ major depressive disorder

■ melancholia

■ eugenics

■ neurotransmitters

■ Freud

■ Beck

Throughout history, our understanding of the causes of mental health problems have changed dramatically, from early theories about demonic possession to complex understandings about the impact of our life experiences. These understandings are of vital importance, as the explanations we give about why someone is distressed has implications for the treatments offered. By tracking the history of what is now called ‘major depressive disorder’ we can see how different explanations for mental health issues have resulted in a range of proposed solutions. Using this example, we can see how our current treatments depend heavily on how we understand ‘the problem’.

Depression throughout history

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 uses the term ‘major depressive disorder’ to describe an ongoing experience of low mood and loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities. To receive a diagnosis, low mood must be accompanied by experiences such as fatigue, changes in appetite, and feelings of worthlessness.

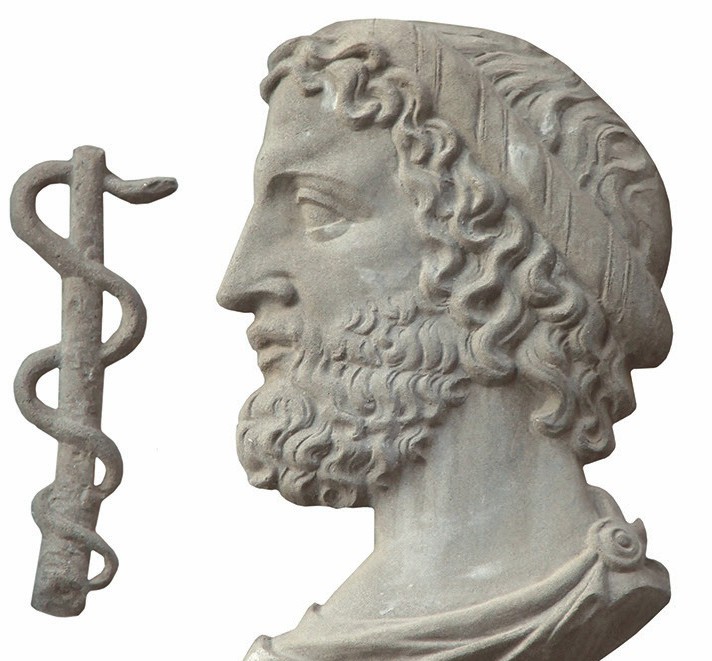

While the label ‘depression’ is relatively new, descriptions of similar conditions can be traced back to around 400 BC, when the term ‘melancholia’ was first used by the Greek philosopher, Hippocrates. Written accounts from this period speak of melancholia being caused by demonic forces and spiritual possessions, with proposed treatments including beatings, physical restraints and starvation to rid the body of demons. Hippocrates believed that melancholia was caused by imbalanced bodily fluids including bile, phlegm and blood, and suggested treatments involving physical activity, good diet, music, baths, and opium-based medications to redress the balance of the body.

Melancholia can also be traced to writings from the Middle Ages and Renaissance periods. Early psychological explanations of depression can be seen in work by Robert Burton, who wrote in 1621 that factors such as poverty and loneliness caused depression.

The impact of biological explanations

However, with advances in medical science, theories of evolution and inheritance became popular, and doctors began looking for biological explanations of melancholia. As a result, mental health issues came to be seen as inherited weaknesses of character. This theory was embraced by those who supported the eugenics movement: the idea that undesirable characteristics could be removed from a population through selecting who was allowed to have children, in order to create a superior human race.

This understanding of depression resulted in many people being removed from society and held in institutions, as well as the use of forced sterilisation to prevent perceived weaknesses from being passed on to children. These ideas were most horrifically enacted during the Second World War by the Nazis, when around 275,000 murders and 400,000 forced sterilisations of people with mental health difficulties were carried out.

By considering these examples from ancient to more recent history, we can see that different understandings of depression have resulted in vastly different consequences for individuals for treatment, as well as for society. Beliefs that depression was caused by problems located within the individual, whether spiritual or inherited, resulted in dangerous and catastrophic solutions. Individuals found themselves cut off from society, with consequences ranging from stigma and ostracism to crimes against humanity.

Descriptions of similar conditions can be traced back to around 400BC, when the term ‘melancholia’ was first used by the Greek philosopher, Hippocrates

Biopsychosocial model of depression

In the twenty-first century, we often speak of the ‘biopsychosocial model of depression’. This suggests that depression is due to a complex interaction between biological, psychological and social factors. However, fierce debate exists as to how much each of these factors impacts on depression and, as we have seen, how we understand ‘the problem’ has enormous implications for how we treat it.

Many believe that the main causes of depression are biological, suggesting that depression is an illness that, like a physical health condition, is caused by physiological malfunctions. These ideas can be traced to Emil Kraepelin in the early twentieth century, and huge quantities of research funding continue to be provided annually in search of biological causes of depression.

Chemical imbalance theory

The biological approach has led to many avenues of research, the chemical imbalance theory of depression is one of the most wellknown. This is the idea that imbalances in the levels of the neurotransmitters serotonin and dopamine in the brain are responsible for the low mood, loss of pleasure and lack of motivation seen in individuals experiencing depression.

Despite huge investment in this research, no one has been able to robustly demonstrate that a neurochemical is responsible for causing depression, and so the idea of a ‘chemicalimbalance’ has been repeatedly de-bunked (Leo and Lacasse 2008). Despite this, medical treatments for depression aimed at altering neurochemistry are extremely common, including a range of medications commonly known as antidepressants. It appears that medications are useful for some individuals because they temporarily boost mood and therefore allow individuals to engage with more rewarding aspects of their lives. However, these improvements are not due to the medications treating any underlying medical illness or addressing a chemical deficiency.

Cognitive theory

In contrast, research has repeatedly confirmed the impact of social and psychological factors in causing depression. Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud proposed the idea that melancholia was a psychological response to loss, and while his work has faced many criticisms, he stressed the importance of a person’s experiences and relationships, both of which have repeatedly been shown to be vital in understanding depression.

These ideas were then taken forwards by others, including Aaron Beck, who believed that our life experiences influence our beliefs about ourselves, the world and other people, generating his cognitive theory of depression in the 1970s. Both Freud and Beck believed that the most effective treatment for depression was talking therapy, where a skilled therapist can help a client to understand and adapt their ways of thinking and interacting with the world. To this day, Beck’s ideas are a vital part of cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) which has remained the most common treatment for depression.

Depression can be understood as a natural reaction to difficult life experiences and restricted life chances

Adversity

Some of the most consistent and reliable research in psychology demonstrates the impact of adversity on mental health. Poverty, abuse, exposure to crime, oppression and marginalisation, including racism, dramatically increases a person’s likelihood of experiencing depression. From this perspective, depression can be understood as a natural reaction to difficult life experiences and restricted life chances, and the causes of depression can thus be linked to the problems within the environments, communities and societies in which people live.

As a result, the potential solutions that are suggested by those who adopt this perspective on depression are vastly different to those suggested by biological and cognitive psychologists: instead of medication or personal therapy, this perspective requires community and societal interventions to reduce social inequalities and work towards social justice.

Conclusion

Throughout history, our understandings of mental health difficulties have had a huge impact on how individuals experiencing depression have been treated. The belief that depression was caused by demonic possessions and weak character allowed for the appalling abuse of large numbers of people. If we believe that mental health difficulties are caused by biological or internal problems within the individual, then our treatments will naturally focus on developing interventions to rebalance that person’s neurochemistry or way of thinking.

Therefore, whether we locate ‘the problem’ within the person or in their environment will have implications for where and how we personally or as a society use our resources. If we believe that people’s distress is a natural reaction to the world around them, as a way to cope with experiences of loss, trauma, poverty, stress and oppression, then the treatment would naturally involve the creation of fairer, safer and more connected societies.

We have come a long way in our understanding of depression. However, when we consider the future of mental healthcare, how we understand the problem of depression will have a significant impact on the solutions we pursue, and the care people receive.

PsychologyReviewExtras

Go to www.hoddereducation.co.uk/psychologyreviewextras for a quiz to check your understanding of this article.

RESOURCES

American Addiction Centres (2020) ‘Historical understandings of depression’. Available at: www.tinyurl.com/9288r3wx.

Leo, J. and Lacasse, J. R. (2008) ‘The media and the chemical imbalance theory of depression’, Society, Vol. 45, No. 1, pp. 35–45.