The US Supreme Court

Is the Supreme Court now the pre-eminent branch of government in the USA?

EXAM LINKS

AQA The nature of judicial power; the significance of judicial review; the significance of the judiciary; checks and balances.

Edexcel Supreme Court: the extent of the power and the effectiveness of checks and balances; relationships between the presidency, Congress and the Supreme Court.

Events in recent years have provided students of politics with countless precedents on an unparalleled scale – from presidential and prime ministerial power to legislative, constitutional and civil liberties activity, the likes and scale of which have rarely been seen in modern times. Judicial activity – its power and scope in the UK and USA – has been equally remarkable.

The activity of the United States Supreme Court in the 2020s has been particularly noteworthy. In May 2022, one of the biggest scandals in recent history rocked the US Supreme Court, when a draft of the majority opinion in the case of Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization was leaked, indicating that the Court was poised to overturn the federal right to an abortion in the USA by a 5–4 majority (Box 1).

Box 1 Dobbs opinion

Excerpt from the leaked draft opinion of Justice Samuel Alito in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, May 2022:

‘Roe was egregiously wrong from the start. Its reasoning was exceptionally weak, and the decision has had damaging consequences.’

In late June 2022 the Court’s ruling duly came, when it held that the Constitution of the USA does not confer a right to abortion. In doing so, the Court overturned two previous rulings, in Roe v Wade (1973) and Planned Parenthood v Casey (1992), to give individual states the power to regulate any aspect of abortion not pre-empted by federal law.

The leak, the ruling, the opinion and the aftermath dominated US national headlines for several months and prompted widespread protest, reflection and recrimination. The judicial crisis that engulfed America perfectly encapsulated the importance of understanding the relationship and balance of power between the branches of government in the USA. This question draws on a range of topics within the A-level politics specification, requiring a synoptic approach.

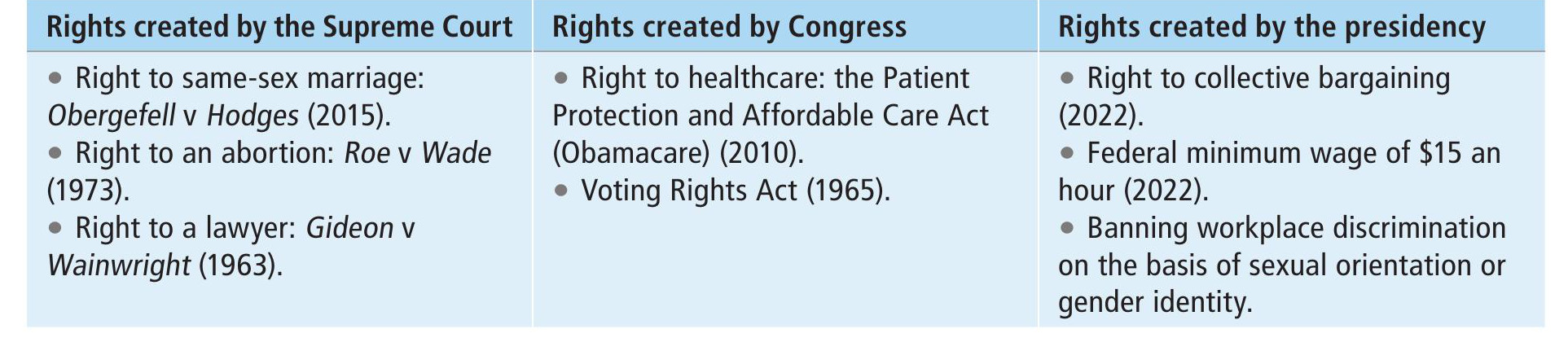

The power to create rights

The fundamental rights of US citizens are laid out in the Bill of Rights – the first ten amendments to the US Constitution. However, these are by no means the only rights a citizen has. Congressional law, presidential executive orders and state law can all give or take away rights in the USA (Table 1). Some of the most controversial rights, such as the federal right to an abortion, have been decided by the Supreme Court, seemingly indicating its power to effectively decide on the sovereignty of this right.

Nonetheless, the Supreme Court hears relatively few cases each year, and this number has declined during the tenure of Chief Justice John Roberts, now hearing on average around 75 cases a year. The vast majority of these cases will not be about the rights of citizens, meaning their impact is limited. Similarly, Congress can create rights through legislation but pass relatively few laws a year. However, Congress can make law at any time, on almost any policy area, having fewer limits therefore than the Supreme Court. The president may be able to create rights through executive orders, but these are only supposed to interpret law, not create new law.

So, while the Supreme Court upheld Obamacare in 2011 and again in California v Texas in 2021, it was actually Congress who passed this law, recommended to them by President Obama, who won his electoral mandate campaigning on this issue. The Court, therefore, can have a huge influence over rights, but its scope is more limited than the other branches of government and its impact tends to be narrower.

Interpreting the Constitution

For the Constitution to remain relevant, it is necessary for some level of interpretation to take place. In this way, the Supreme Court can exercise considerable power. If the other branches of government are deemed to have acted unconstitutionally, the Supreme Court can strike down their laws or actions (Box 2).

Box 2 The power of the Court

Charles Evans Hughes, a US Supreme Court Justice in the 1930s, commented on the Court’s role of constitutional interpretation:

‘We are under a Constitution, but the Constitution is what the judges say it is.’

Congress could pass a constitutional amendment to overturn a Supreme Court ruling. By changing the document, they would change the Court’s interpretation. But the amendment process is so difficult that this happens rarely, and it seems even more unlikely in an era of hyper-partisanship. Of nearly 12,000 suggested amendments, only 27 have passed – which leads to questions about the effectiveness of this process.

Both the president and Congress can try to influence the Court’s interpretation of the Constitution through the filling of vacancies that arise. Presidents will nominate justices who appear to have a similar ideology to them. Biden’s appointment of Ketanji Brown Jackson was born out of his desire to maintain representation on the Court, both in terms of sex and race, and because her previous rulings seemed to be liberal. However, this balance can only be affected when vacancies arise, and once someone is on the Court, there is no guarantee of how they will vote. In interpreting the Constitution, the Court seems to hold a balance of power which the other branches of government can find difficult to challenge. Nonetheless, in hearing so few cases a year, they appear to be very powerful but in relatively narrow policy areas.

The power to overrule Congress

The Supreme Court can strike down congressional (and state) laws if they are deemed to be unconstitutional. In the case of Obergefell v Hodges (2015), the Court struck down the Defense of Marriage Act, making same-sex marriage a federal right in the US. The extent of this power is especially controversial, as overruling congressional law means overturning the electoral mandate of both Congress and the president.

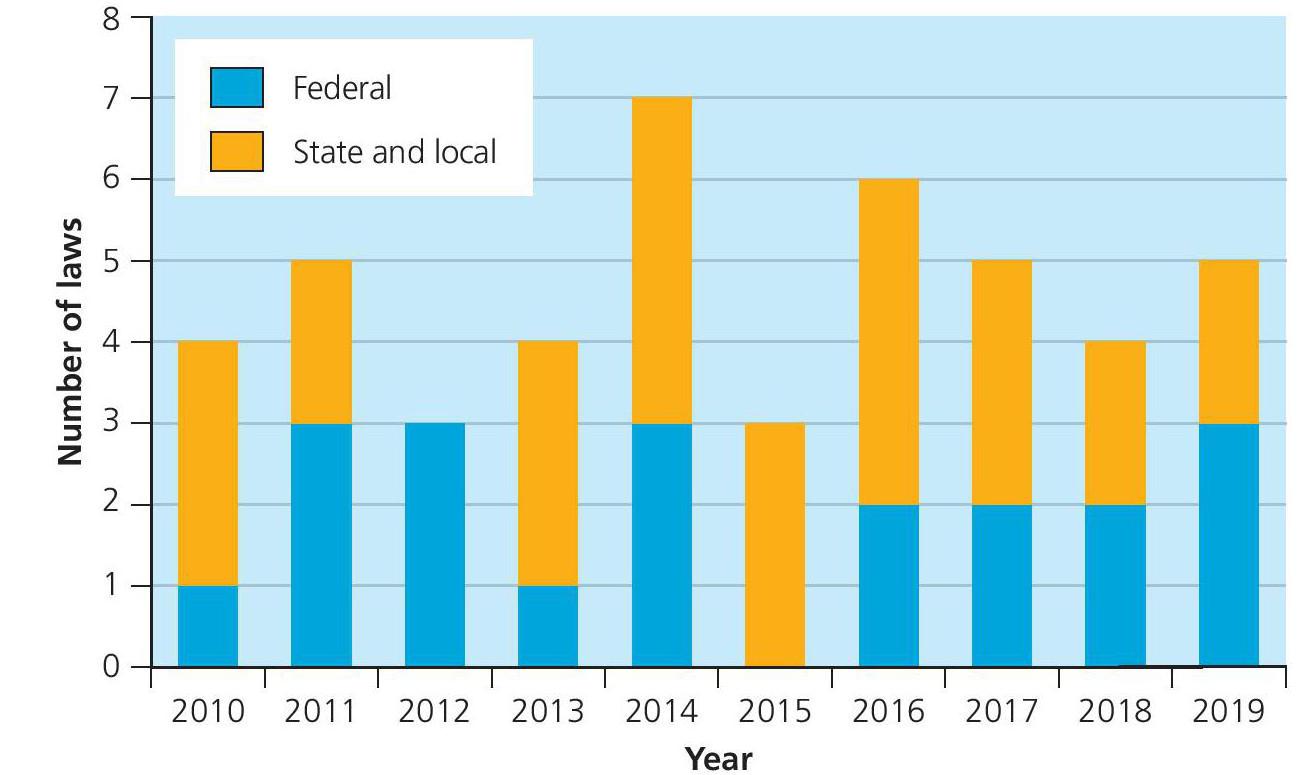

However, this is limited not only by the number of cases the Court hears each year, but also by the time it can take a case to work its way through the legal system and up to the US Supreme Court. The Defense of Marriage Act was passed in 1996, nearly 20 years before this ruling. Looking at the figures of state and federal laws overturned by the Supreme Court each year (Figure 1), it seems that the likelihood of the Court using its power over Congress is minimal, thereby limiting its ultimate influence.

Figure 1 Laws held unconstitutional in total or in part by the US Supreme Court

The power to overrule the president

Actions taken by the president can be ruled constitutional or not by the Supreme Court. In 2022, the Court ruled against President Trump, who had argued that he did not need to release documents related to the 6 January insurrection at Congress, as they were protected by executive privilege. This was all the more surprising because the Court at this time consisted of six ‘conservative’ justices, three of whom were Trump appointees. This interpretation of the Constitution suggests that executive privilege is not without limits and upholds the importance of Congressional oversight on the executive branch.

The likelihood of the actions of a president being found unconstitutional are, however, relatively slim. It happened to President Obama regarding recess appointments and to President Bush regarding Guantanamo Bay, but such instances are infrequent.

Limitations on the Court

There are both informal and formal limitations on the power of the Court that further limit its ability with regards to its power over Congress and the president. The Court conventionally follows the principle of stare decisis, meaning that a previous Court decision should usually be allowed to stand. This is not binding, and the Court routinely needs to update those decisions which have become outdated in a modern society. Nonetheless, the principle is well known and when the Court breaks it, it usually has to explain why – as Alito did in his leaked draft of Dobbs v Jackson.

court was hearing arguments in the Dobbs case, December 2021

Similarly, the Court cannot enforce its own ruling, instead relying on the government itself or states. Following the 2010 ruling of Citizens United v FEC, President Obama accused the Court of opening the floodgates to special interests, with Alito in the audience mouthing ‘not true’. Regardless of his opinion, however, Obama did follow the Court’s ruling.

Conclusions

The power that the Supreme Court has in the US government seems to follow a common theme: the possibility of a big impact but with relative infrequency. Landmark cases amount to single figures each year, with notable examples making headlines but in relatively narrow policy areas. Nonetheless, as hyper-partisanship grips Congress, making it more difficult to pass meaningful legislation, there is no doubt that in the last 10 years the Supreme Court has made a number of substantial decisions which do seem to have challenged the power of the president and Congress. In the case of Dobbs v Jackson, the furore over the leak and eventual decision served to demonstrate the power of the Court, while undermining its legitimacy.

ACTIVITIES

Class discussion

1 Which branch of government has the most significant constitutional powers?

2 Why is the power of constitutional interpretation significant for the Supreme Court?

3 Outline the extent to which the ideological balance of the Supreme Court affects policy outcomes.

Independent research

1 Research the cases of NFIB v Sebelius and California v Texas, highlighting the powers of each branch of government.

2 Research the ideological balance of the Supreme Court since 2005 and evaluate any impact this has had.

EXAM-STYLE QUESTIONS

1 ‘The US Supreme Court faces greater limits on its powers than the UK Supreme Court.’ Analyse and evaluate this statement.

(25 marks, AQA-style)

2 Evaluate the view that the Constitution has failed to effectively separate the powers of the US government.

(30 marks, Edexcel-style)