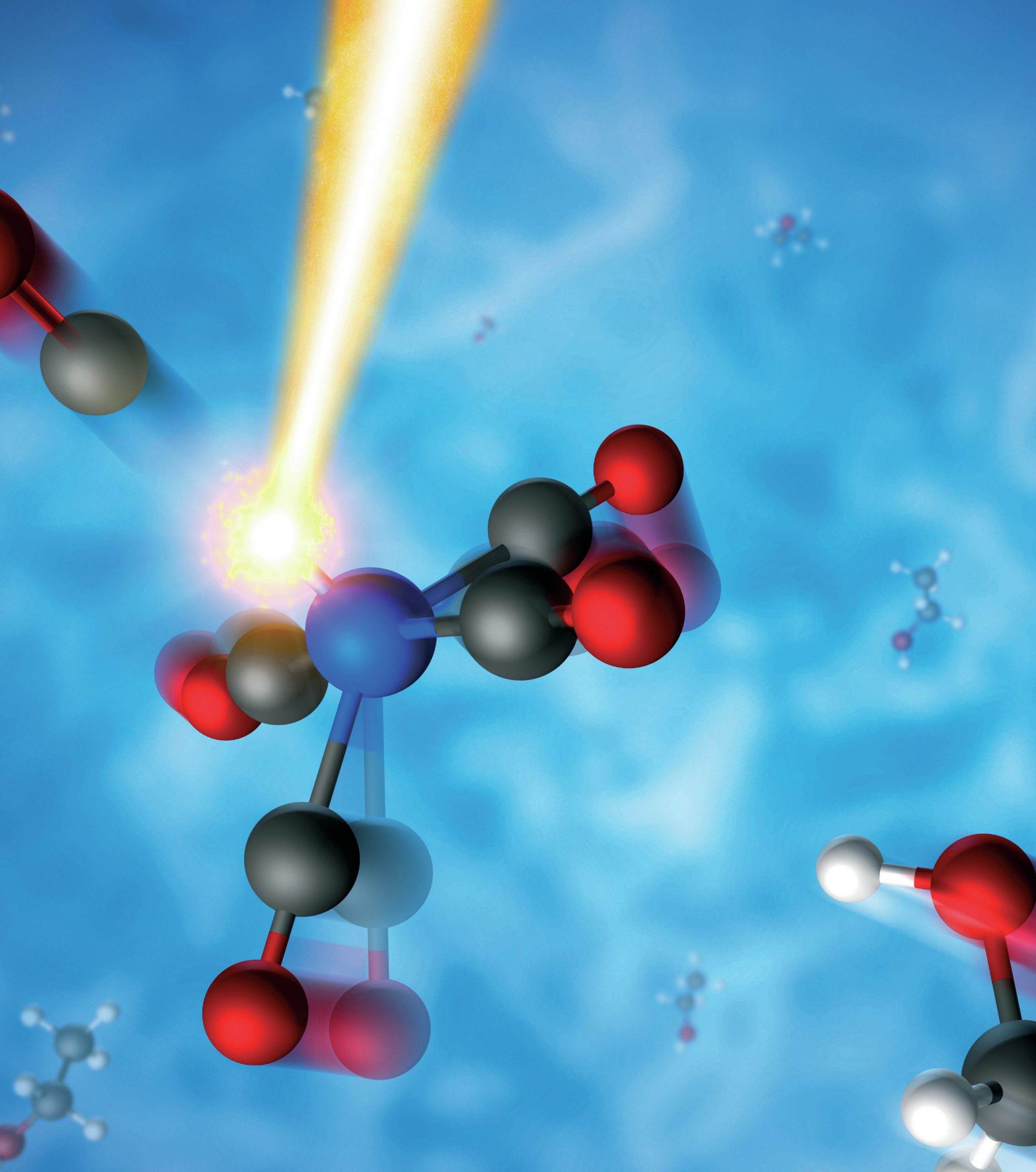

In May 2016 scientists at Stanford University in the USA published a movie showing an X-ray pulse vaporising a water droplet (Figure 1). The movie was produced with the world’s most powerful X-ray laser, the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), which delivers bursts of X-rays lasting just 10 femtoseconds (10 × 10−15s = 10 −14s), allowing very rapid, small-scale processes to be tracked and imaged. The LCLS can even produce stopframe images of molecules in motion (Figure 2). The LCLS has been so successful that a similar instrument has been built in Japan and there are plans to build a high-power X-ray laser for Europe based in Hamburg, Germany.

In this issue you can read about a ground-breaking use of X-rays that would have been worthy of a Nobel prize (‘Not the Nobel prize in 1916’, pp. 18–21), and about the experiments that first demonstrated that X-rays can collide like particles (‘The Compton effect’, pp. 6–9).

Your organisation does not have access to this article.

Sign up today to give your students the edge they need to achieve their best grades with subject expertise

Subscribe