What we mean by ‘north’ is a matter of convention. However, it was recognised long ago that certain materials, such as the mineral lodestone, point towards what we now call Earth’s north and south poles (as defined by Earth’s rotation axis). Because the north pole of a magnet points ‘north’, the magnetic pole at the north geographic pole has to be a south magnetic pole.

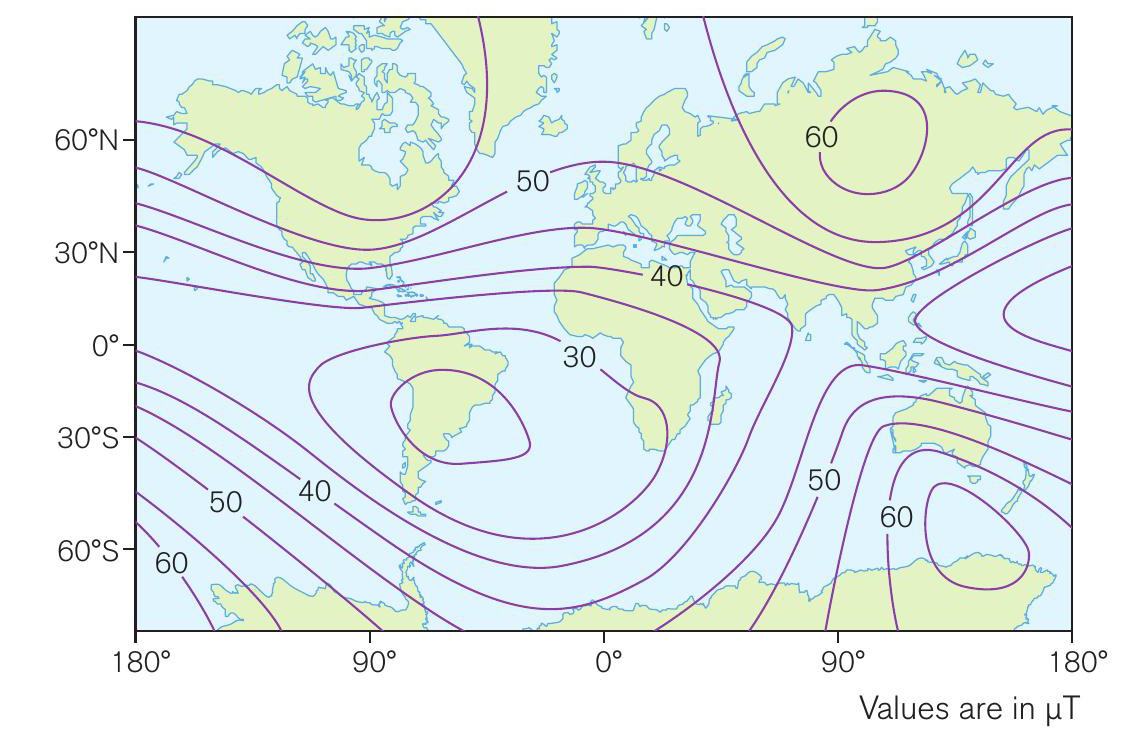

To a fair approximation, Earth’s magnetic field is similar to that of a bar magnet with two magnetic poles; we call this a dipole. However, the Earth’s field is a lot more complex; it varies in size at different places (Figure 1) and changes over time. Measurements made in London in 1580 showed the magnetic pole to be 11° to the east of the geographic pole. By 1660 the angle of declination was 0°, i.e. true north and the magnetic pole were in the same direction. Still from London, by 1820 the declination was 24° to the west. This is an extremely rapid change compared to geological changes, which can take millions of years. Not only is the magnetic pole drifting, but also the field has completely reversed many times during the history of the Earth. Studies of rocks indicate at least 177 reversals during the last 85 million years — about once every 480 000 years (Figure 2). Any theoretical model must explain these variations (see How science works, pages 29–31, for more about models and theories).

Your organisation does not have access to this article.

Sign up today to give your students the edge they need to achieve their best grades with subject expertise

Subscribe