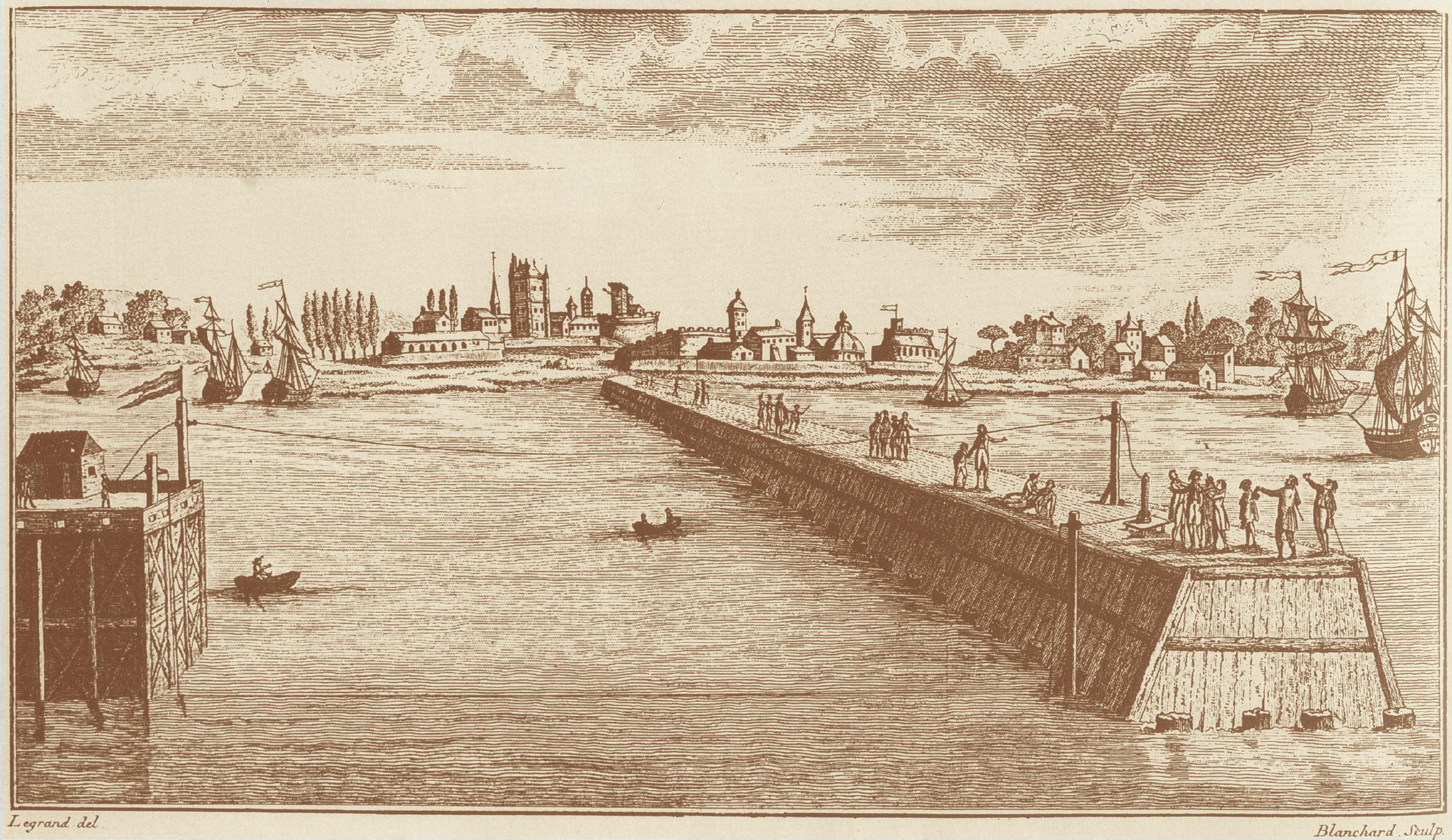

In 1803, Italian physicist Giovanni Aldini (1762–1834) set out to determine the speed of an electric current. He set up a battery made from 80 silver and zinc plates on a jetty in Calais harbour, and connected it to a circuit of conducting wire running via the Red Fort (far left in Figure 1) to a hut on another jetty. In the hut was Aldini’s current detector — a dissected animal that would register an electric shock. The circuit was completed by an overhead wire. When this was attached to the battery, a man near the hut immediately signalled that the animal’s muscles had twitched, and Aldini concluded that the current had travelled ‘with astonishing rapidity’.

Through a combination of theory and experiment, we now understand that current in a metal is due to the motion of large numbers of mobile electrons (Figure 2). If there are n mobile electrons per unit volume, each with charge e, moving at an average velocity v in a wire of cross-sectional area A, then the current I is:

Your organisation does not have access to this article.

Sign up today to give your students the edge they need to achieve their best grades with subject expertise

Subscribe