On 22 December 1864, Union general William Tecumseh Sherman sent President Abraham Lincoln a short telegram: ‘I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the city of Savannah.’ Commanding 60,000 Union soldiers, Sherman had accepted the surrender of the city at the end of a 300-mile trek through Georgia, known as the March to the Sea. Sherman’s army had faced little opposition from Confederate forces during this campaign, suggesting that after three and a half years of war, Confederate defeat was in sight.

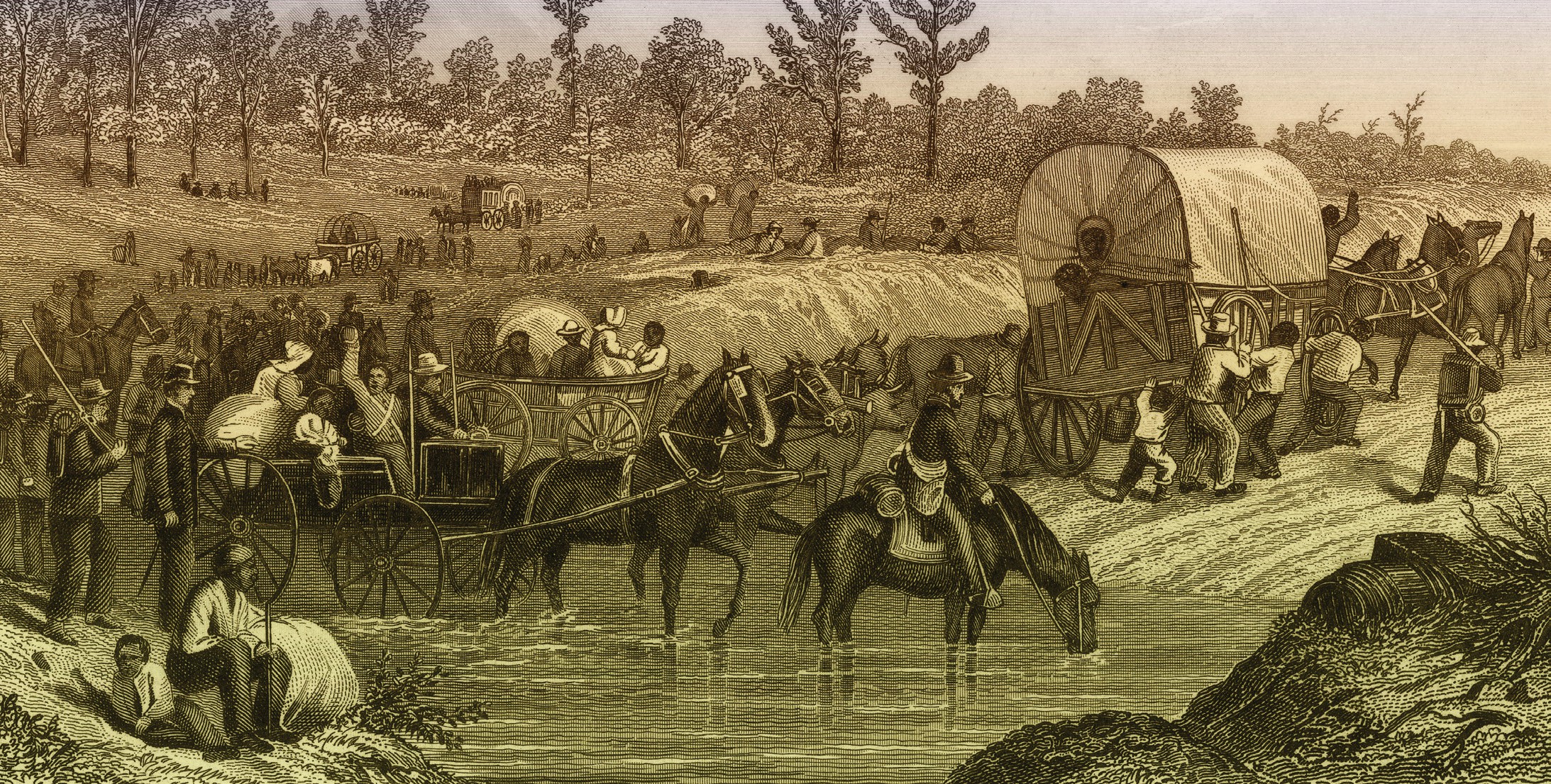

Sherman’s army had also become a de facto army of liberation, as nearly 18,000 enslaved African Americans saw the Union banner as a signal to abandon the plantation and followed Sherman’s forces to Savannah. Far from an abolitionist, Sherman saw these black refugees as a burden on his command, what he described as ‘a growing encumbrance’. Some of Sherman’s subordinates were actively hostile to emancipation: the general commanding one of Sherman’s flanks had prevented 600 black refugees from following his men across Ebeneezer Creek, allowing them to be captured by pursuing Confederates or drown in the freezing water.

Your organisation does not have access to this article.

Sign up today to give your students the edge they need to achieve their best grades with subject expertise

Subscribe