Activism in Notting Hill

Scott Reeves considers the impact seven Notting Hill activists had on British society

Source A Claudia Jones at the offices of the West Indian Gazette in 1962

EXAM LINKS

AQA Britain: migration, empires and the people: c.790 to the present day

Edexcel Notting Hill, c.1948–c.1970

Eduqas Austerity, affluence and discontent: Britain, 1951–1979

OCR (A) Migration to Britain c.1000 to c.2010

OCR (B) Migrants to Britain, c.1250 to present

WJEC Changes in patterns of migration, c.1500 to the present day

By the end of the Second World War, the once wealthy London suburb of Notting Hill was rundown and ramshackle. Large homes that had once housed middle-class families were subdivided into shabby slums. When migrants started to arrive in Britain, particularly from the Caribbean, they found Notting Hill was one of the few areas they could afford and landlords were prepared to rent to them. Yet these bleak surroundings inspired a generation of political activists to mold their beliefs and take action to improve their lives.

Claudia Jones

Jones was always interested in political activism. Born in Trinidad and Tobago, she emigrated to the USA but was deported from there in 1955 for being a member of the US Communist Party. When the governor of Trinidad and Tobago refused to take her back, she claimed asylum in Britain.

Three years after landing in the UK, Jones launched a newspaper, the West Indian Gazette. Widely regarded as Britain’s first black newspaper, the Gazette quickly gained 15,000 readers, although it always struggled to make a profit and closed in 1965. During the 8 years it was printed, the newspaper reported on events in the Caribbean and across the world, but it also promoted the achievements of black actors, musicians and entertainers in Britain and reported incidents of racist violence.

In November 1958, in response to race riots, Jones suggested an event be organised to ‘wash the taste of Notting Hill and Nottingham out of our mouths’. A Caribbean Carnival featuring music, dancing and a beauty pageant was hastily organised and took place in January 1959 at St Pancras Town Hall. Jones wanted to unite the community and some of the money raised helped pay the fines that both black and white youths incurred in the Notting Hill race riots.

Source B

Claudia Jones writing about the West Indian Gazette in 1964:

The newspaper has served as a catalyst, quickening the awareness, socially and politically, of West Indians, Afro-Asians and their friends. Its editorial stand is for a united, independent West Indies, full economic, social and political equality and respect for human dignity for West Indians and Afro-Asians in Britain, and for peace and friendship between all Commonwealth and world peoples.

Source C The Caribbean Carnival held in January 1959

Rhaune Laslett

The daughter of a Native American mother and a Russian father, Laslett was born in London and set up a children’s playgroup in Notting Hill to bring together families of all races and nationalities. In March 1966, working with other community leaders, Laslett helped set up the London Free School. This was an informal adult education network in which people with specific skills like painting, music, photography and film would tutor others. Much like the playgroup, the Free School was designed to welcome people from across the community, regardless of their skin colour or ethnicity.

Laslett helped found a festival to help promote the Free School and raise its profile. The Notting Hill Fayre and Pageant, like the Caribbean Carnival before it, featured music and entertainment, but on a greater scale. The week-long festival in September 1966 culminated in a parade through the streets.

Between them, Laslett’s Notting Hill Fayre and Jones’ Caribbean Carnival were precursors of the Notting Hill Carnival, now the largest street party in the country.

Another offshoot of the Free School was the Notting Hill Neighbourhood Service, a group of volunteers that offered people advice on drugs, money and the law. The self-help network aimed to improve the lives of residents in Notting Hill by intervening before people ran out of money or got into legal trouble.

Source D

Rhaune Laslett writing about the Notting Hill Fayre and Pageant in the London Free School newsletter:

We felt that although West Indians, Africans, Irish and many other nationalities all live in a very congested area, there is very little communication between us. If we can infect them with a desire to participate then this can only have good results.

Michael X

Whereas Jones and Laslett wanted the different racial groups of Notting Hill to work together, others thought it better to divide them further when necessary. Among them was a migrant from Trinidad and Tobago named Michael de Freitas. He was initially an enforcer for Peter Rachman, a notorious slum landlord. His official job was to collect rents, but he would threaten and intimidate people who Rachman wanted out, even resorting to killing pets and dumping people’s property into the streets.

However, de Freitas gradually turned his back on his unsavoury past and began helping out at the London Free School and other community organisations. After meeting the black American activist Malcolm X, de Freitas began to refer to himself as Michael X. He set up the Racial Adjustment Action Society (RAAS), a pro-black organisation that grew to 45,000 members. He invited boxing world champion Muhammad Ali to visit Laslett’s playgroup and the Free School when he fought in London in May 1966.

However, the RAAS supported the use of violence to achieve black equality. In 1967, Michael X — who took the name Michael Abdul Malik after converting to Islam — was arrested following a RAAS meeting in Reading and sentenced to a year in prison for breaching the Race Relations Act. He had told the crowd: ‘If you ever see a white laying hands on a black woman, kill him immediately.’ He was the first black person to be jailed for attempting to stir up racial hatred — an offence usually committed against black people, not by them.

Michael X was a divisive figure and many activists in Notting Hill shunned him. He left London in 1971 and was later executed in his native Trinidad and Tobago for murder.

Source E

Two views of Michael X:

He was a visionary right, this Carnival is down to Michael you know. Down to Michael because what happened was those guys decided to come on the road one day and they following he, and the next thing he’s talking to this woman who’s running a neighbourhood thing down on Tavistock Road, Ronnie Laslett, and they twos up. And that kick off from there.

A resident of Notting Hill

Michael X was quite simply a hustler, who was hustling off of Malcolm X’s name. He was a crook! He didn’t set up anything you could commit to — he didn’t organise anything political.

Darcus Howe

Bruce Kenrick

Born in Liverpool, white church minister Kenrick spent time in the USA before returning to the UK and moving to Notting Hill in 1963. Shocked by the state of accommodation that people were forced to live in, Kenrick decided to set up a housing association similar to those he had seen in New York. The Notting Hill Housing Trust (NHHT) aimed to buy property, renovate it and rent it out at a fair price.

The NHHT exploded in 1964 after Kenrick used a £7,000 donation on newspaper advertising. Donations flooded in, dwarfing the initial sum that paid for the adverts. Within a year, the NHHT had five new properties housing 57 renters. Donations continued to pour in and the NHHT soon became a major landholder in Notting Hill. No longer were the area’s poorest residents dependent on slum landlords whose primary aim was to fleece their tenants for as much money as possible.

Source F

John Coward, a director of the Notting Hill Housing Trust, in an obituary for Bruce Kenrick:

Bruce’s contribution was inadequately recognised during his lifetime. But it is incontestable that thousands of families now enjoy the benefits of decent accommodation as a result of his intervention in the housing scene.

Courtney Tulloch

A 24-year-old Jamaican who settled in London in 1966, Tulloch quickly became a respected community leader. He helped in the creation of the London Free School and the People’s Centre, another community organisation designed to help different races and nationalities. He also spearheaded Defense, an organisation providing legal aid and advice to black people.

Tulloch was a journalist too and helped to raise awareness of racism in Notting Hill and Britain as a whole. He set up the Hustler, a fortnightly newspaper that reported racist abuse and attacks. He also wrote for the International Times, acting as editor for a time, although he was never officially named to the position since the authorities tried to clamp down on the paper and put it out of business.

Source G

Naseem Khan, a writer for the Hustler:

We were certain that the Hustler should base itself on independent ground. This meant we could have a broad reach…But its independence was not always popular. One of my clearest memories is of Courtney’s immediate resistance when activists threatened to run the Hustler off the streets because it also included white interests.

Darcus Howe

Among the writers who contributed to the Hustler was Howe, a former law student who was a regular at political meetings in Notting Hill and formed the Black Eagles in 1968. The Eagles campaigned for better housing, the release of black political prisoners and the right for black people to be tried by an all-black jury. Howe thought that one of the biggest barriers facing black people in Notting Hill were the police, who he regarded as racist. The Black Eagles patrolled the streets and observed the police, gathering evidence of police brutality and harassment. The Eagles antagonised the Metropolitan Police and officers often turned their attention to the Black Eagles themselves.

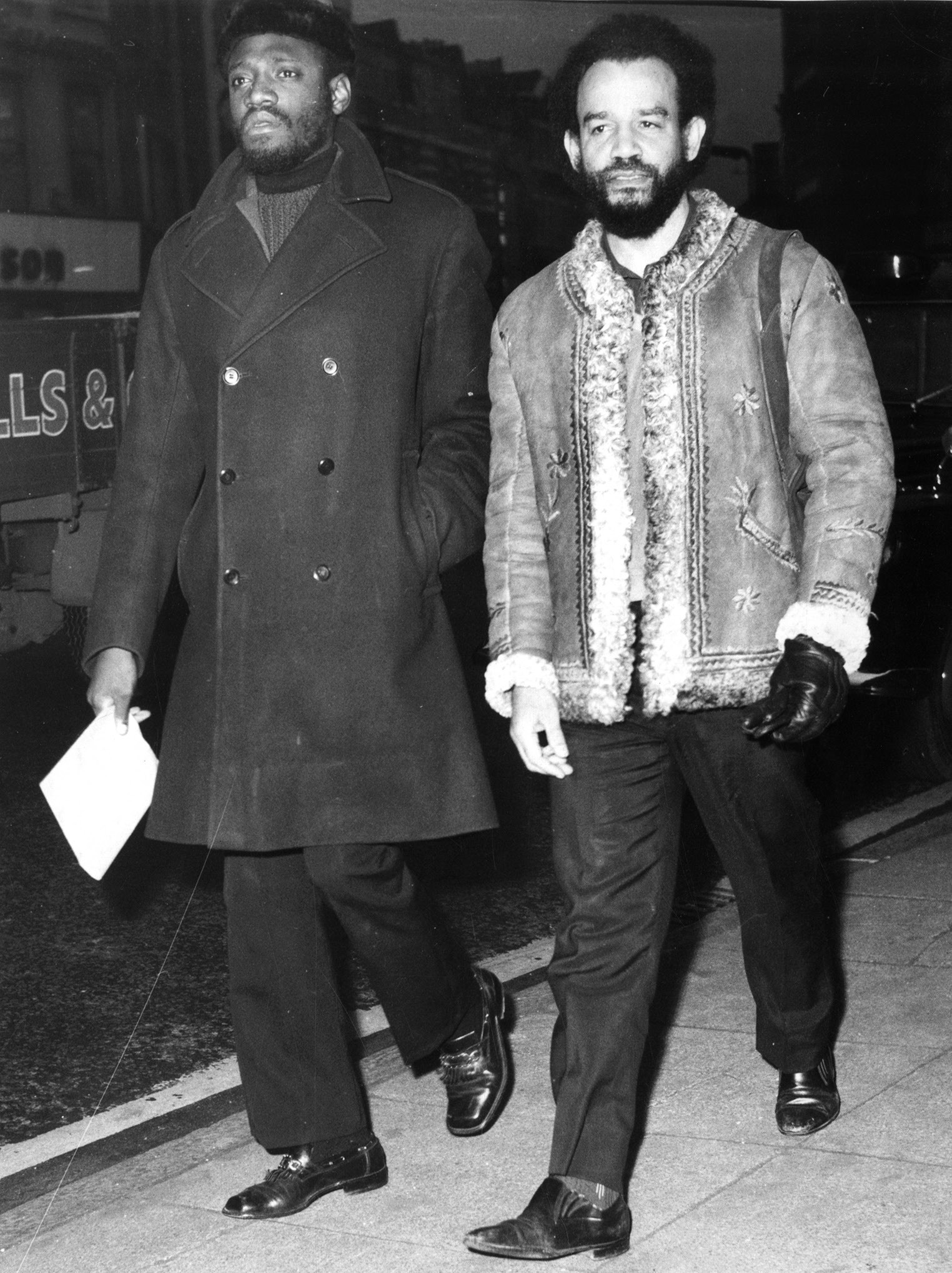

Source H Darcus Howe and Michael X in 1968

The Eagles were short-lived, lasting only 5 months, and Howe soon joined a similar organisation, the British Black Panthers. The Panthers had similar aims to the Eagles and had around 3,000 members by the 1970s, mostly in Notting Hill and the surrounding areas.

Frank Crichlow

The British Black Panthers’ most notable campaign came in 1970. Fed up with the police targeting the Mangrove, a restaurant frequented by many activists and celebrities in Notting Hill, Mangrove owner and Black Panther member, Frank Crichlow, organised a protest march on 9 August. He had endured years of police raids on his premises. The officers claimed they were looking for drugs — despite it being common knowledge that Crichlow was very anti-drugs — or minor infringements like serving food after 11pm.

Demonstrators marched past three police stations with a pig’s head and chanted anti-police slogans. When scuffles broke out near the third station, the police arrested 19 people. Nine people, including Crichlow and Howe, faced trial for the serious offence of inciting a riot, but the judge dismissed the charges — he said the protestors’ shouts of ‘Kill the pigs’ was not a genuine threat to police officers.

However, the case returned to court when the government took the unusual step of overturning the judge’s decision. The ‘Mangrove Nine’ were found innocent by a jury in a case that was covered by newspapers across the country. Although Crichlow initially wanted to make sure his restaurant was not unfairly targeted by the police, his trial made people aware that racism within the police was a genuine issue.

Perhaps he was right — police raids on the Mangrove continued and Crichlow was twice put on trial for the possession of drugs. Both times the jury found him innocent.

Source I

Frank Crichlow remembering the Mangrove Nine trial:

It was a turning point for black people. It put on trial the attitudes of the police, the Home Office, of everyone towards the black community.

Conclusion

Nowadays, Notting Hill is back to being a soughtafter location where wealthy people choose to live. Yet a number of blue plaques on buildings in the area tell the story of a poor suburb in which political activists lived and worked to improve the lives of the migrants and black people who lived there.

Summary

■ Activists living in and around Notting Hill were inspired to improve the lives of its residents.

■ Claudia Jones and Rhuane Laslett founded two of the precursors to the Notting Hill Carnival.

■ The activists were often involved in the same organisations like the London Free School or the Mangrove protests.

■ Some like Bruce Kenrick wanted to help all races and ethnicities and only use peaceful action.

■ Others like Michael X favoured violence and pro-black activism where necessary.

Questions

1 There are seven Notting Hill activists in this article. Rank each in order of their impact on British society.

2 Examine Sources A and B. What do they tell you about the activism of Claudia Jones?

3 How reliable is Source D to a historian studying Notting Hill in the 1960s?

4 Read the extracts in Source E. How do they differ in their opinions of Michael X?

5 Read Source F. What other sources do you think would be useful to study the impact of Bruce Kenrick?

6 Read Source G. How useful is it as a source of information about Courtney Tulloch?

7 Examine Source I. What conclusions can you draw about the police and the Mangrove Nine trial?

8 ‘Of Notting Hill’s activists, Frank Crichlow was the most successful.’ How far do you agree?