Opposition to the Nazi regime

Mark Rathbone examines the nature and extent of opposition in Germany to the Nazis

You could be forgiven for thinking that Hitler was a very popular leader in Germany. The documentary film about the 1934 Nuremberg Rally, Triumph of the Will, which is frequently used in television documentaries about Nazi Germany, shows row upon row of thousands of Germans gathered in a huge stadium to hear and cheer speeches by Hitler and other Nazi leaders. Remember, however, that this film which was directed by Leni Riefenstahl, though widely recognised as an outstanding example of cinematic technique far ahead of its time, was made as a propaganda film to glorify Hitler and to represent the German people as being unified behind his leadership.

EXAM LINKS

AQA Germany, 1890–1945: democracy and dictatorship

Edexcel Weimar and Nazi Germany, 1918–39

OCR (A) Germany 1925–55: the people and the state

OCR (B) Living under Nazi rule, 1933–45

The reality was not so simple. The policy of Gleichschaltung (or ‘coordination’) was designed to align the entire population of Germany with Nazi goals. There was no free press and open criticism of the regime was brutally suppressed by the Gestapo and the Security Service (SD).

Many Germans were Nazi Party members and loyal supporters of the regime. A larger number, despite having no great love for Hitler, were prepared to put up with the less attractive aspects of Nazi rule because the economy in the second half of the 1930s was thriving and Germany appeared to have shaken off the economic crises of the Weimar years. But there was some German opposition to the Nazi state, ranging from casual non-compliance with Nazi regulations at the lower end of the scale to conspiracies to assassinate Hitler at a far more extreme level.

Political opposition

Initially, when Hitler became chancellor of Germany in January 1933, opposition came from progressive parties such as the Social Democratic Party, which had been part of every government coalition during the Weimar Republic from 1918 to 1933, and the Communist Party, which was more left-wing. But these political opponents were quickly dealt with by the new Nazi authorities. The Reichstag Fire in February 1933 was used as a pretext to arrest many leading Communists and the passage of the Enabling Act in March 1933 gave Hitler power to bypass the elected Reichstag and rule by decree. Within weeks, all political parties, except the Nazi Party, had been banned.

1 Look at Sources A, B, C and D.

a Comparing Sources A and B with Sources C and D, what differences were there in the activities of the Swingjugend and the White Rose group?

b How might these differences explain the different ways in which each of the two groups were dealt with by the Nazi authorities?

Source B

Günter Discher, a leader of the Swingjugend, recalling an illicit jam session at Moringen youth detention forced labour camp, where he was imprisoned:

The salt mine where we worked had really nice acoustics. One of us played on the cartridges — these were like wooden boxes, and he would play drums with some sticks. We improvised all sorts of things. Sometimes it sounded horrible. Either way, we had successfully gotten through our so-called breakfast break. It was a survival strategy.

From Music and the Holocaust website: www.tinyurl. com/5xm35au9

The centrist parties, the Social Democratic Party, the Zentrum and the German Democratic Party, had formed a paramilitary wing called the Reichsbanner Schwartz-Rot-Gold as long ago as 1924. Its role had been to defend the Weimar Republic from extremist parties of both left and right, notably the Communists and the Nazi Party. Predictably this too was banned by Hitler soon after he came to power and many of its leaders either fled abroad or were jailed.

The Reichsbanner movement

Yet the remnants of the Reichsbanner movement went underground, continuing to resist the Nazi regime right through until its defeat in 1945. In 1933–34, former police officer, Karl Henrich, and ex-soldier and journalist, Theodor Haubach, built up an illegal, underground, version of the Reichsbanner organisation, which was much smaller than its predecessor, but still had over 1,000 members.

Another former Reichsbanner leader, Walter Schmedemann, formed a separate resistance group and published an underground newspaper. All three men were quickly arrested, though Haubach was unexpectedly released in 1935. He continued to run the underground Reichsbanner organisation, committing acts of sabotage and spying, but after the bomb plot of 1944, he was arrested again and hanged in January 1945. Haubach and Schmedemann, though they spent years in concentration camps and prisons, ultimately survived the war.

Opposition from the young

Opposition to Nazism also came from young people.

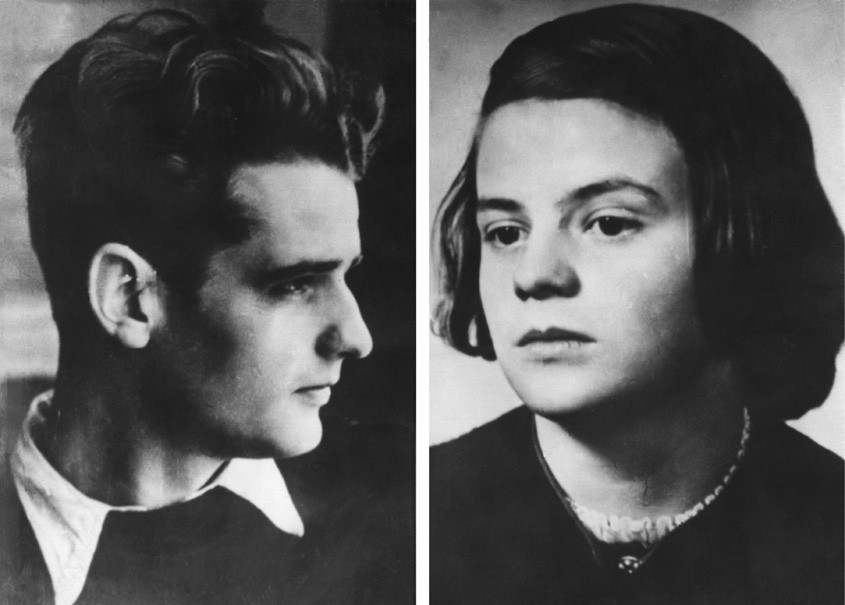

The White Rose group

The best-known example is the White Rose group, formed by students at Munich University in 1942. Its leaders, Sophie Scholl, her brother Hans Scholl and Professor Kurt Huber, were arrested and executed in 1943 for printing and distributing anti-Nazi leaflets.

The Edelweiss Pirates

More widespread, though more loosely organised, the Edelweiss Pirates emerged from a broad-based federation of youth movements, the Bündische Jugend, which had been banned by the Nazis before the war because it was seen as a rival to the Hitler Youth. Becoming increasingly active after the outbreak of war in 1939, these groups of disaffected young people carried out low-key disruption, such as painting anti-Nazi slogans on buildings, but they also typically sheltered deserters from the armed forces and attacked Nazi officials. In 1944, one group of Edelweiss Pirates assassinated the head of the Gestapo in Cologne, which led to vicious retaliation by the Nazi authoriti es, including the public hanging of 12 members of the group.

Source C

Extract from a leaflet distributed at Munich University by the White Rose group, 1942–43:

Our present ‘state’ is the dictatorship of evil. ‘Oh, we’ve known that for a long time,’ I hear you object, ‘and it isn’t necessary to bring that to our attention again.’ But, I ask you, if you know that, why do you not bestir yourselves, why do you allow these men who are in power to rob you step by step, openly and in secret, of one domain of your rights after another, until one day nothing, nothing at all will be left but a mechanised state system presided over by criminals and drunks? Is your spirit already so crushed by abuse that you forget it is your right — or rather, your moral duty — to eliminate this system?…Sabotage in armament plants and war industries, sabotage at all gatherings, rallies, public ceremonies, and organisations of the National Socialist Party. Obstruction of the smooth functioning of the war machine.

Source D

The Swingjugend

The Swingjugend (‘Swing Youth’), originating in Hamburg, expressed their rejection of Nazi values by drinking alcohol, wearing American or British fashions and dancing to American jazz and swing music. Although they were more a counterculture than a political opposition movement, their Anglophile tendencies, desire for freedom and enthusiasm for a style of music which the Nazi regime rejected as ‘degenerate’ and ‘un-German’ led to a clampdown in August 1941.

More than 300 Swingjugend were arrested. Some, such as Günter Discher, were sent to concentration camps for ‘re-education’, but the mass arrests had the reverse effect to what the Nazis intended as they politicised the Swing Youth and their activities began to include distributing anti-Nazi leaf lets.

Christian opposition

Another form of opposition to Nazism came from Christian churches. In 1933, Hitler had made a concordat with the pope. He promised to respect the independence of the Roman Catholic Church and allow Catholics freedom of worship. In fact, he quickly broke this promise, taking over Catholic schools and banning the Catholic Youth League. As a result, some Catholic priests opposed Hitler and in 1937, ‘With Burning Concern’, an encyclical from Pope Pius IX condemning Hitler, was read out in Roman Catholic churches.

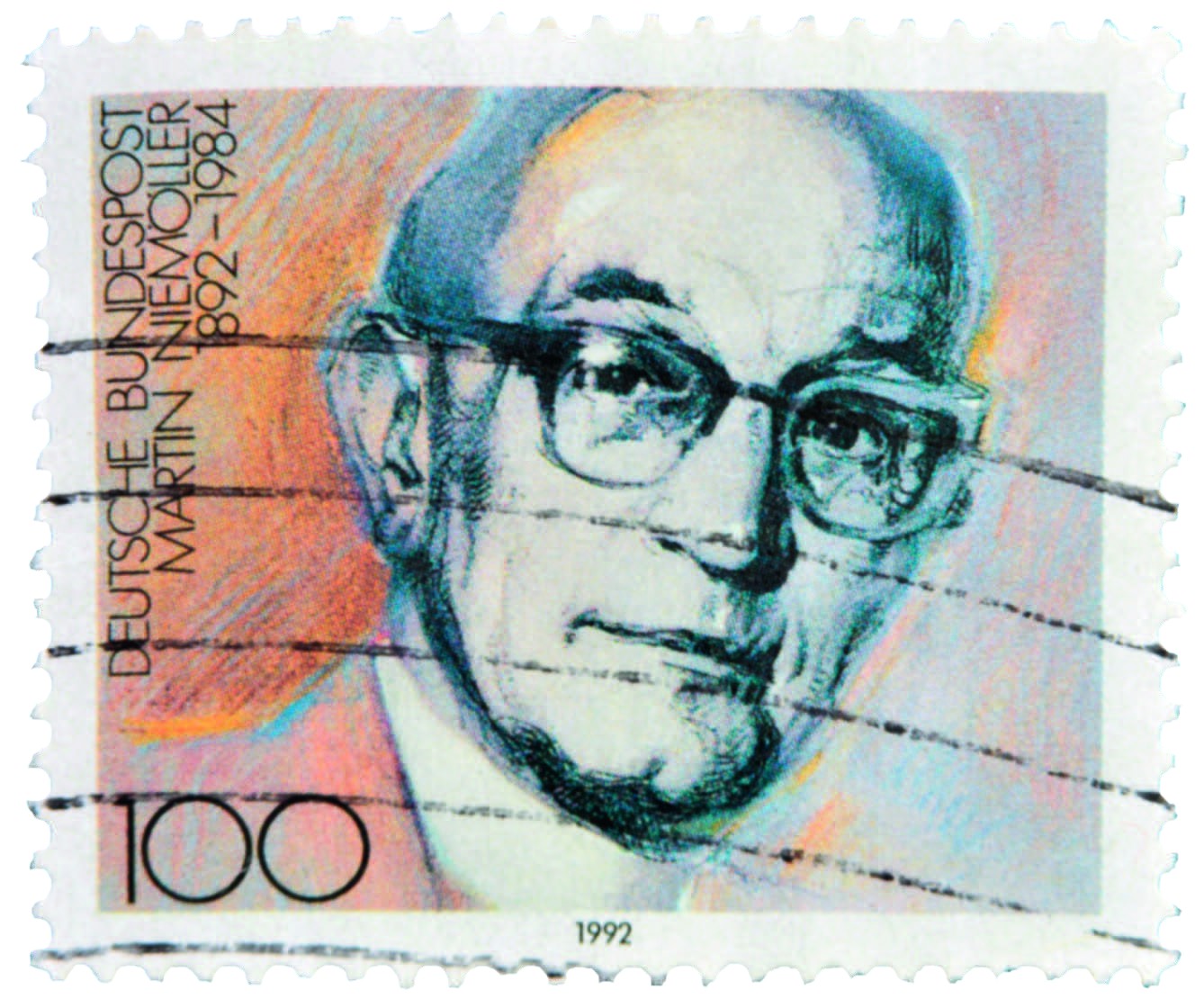

Although Hitler tried to incorporate all Protestant Christians in a Nazi-controlled ‘Reich Church’, some, notably Pastor Martin Niemöller and Pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer, refused and formed the independent Bekennende Kirche (‘Confessing Church’) which openly criticised Hitler. Both were eventually arrested and sent to concentration camps. While Bonhoeffer was executed in April 1945, Niemöller survived imprisonment and was liberated by US soldiers in 1945.

Source E

‘First they came’ by Martin Niemöller, 1946:

First they came for the Communists and I did not speak out because I was not a Communist.

Then they came for the Socialists and I did not speak out because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists and I did not speak out because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews and I did not speak out because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me and there was no one left to speak out for me.

The Kreisau Circle

Several committed Catholics and Protestants were also involved in the Kreisau Circle. This was a small group of mainly aristocratic individuals led by a member of a famous Prussian military family, Helmuth von Moltke, which met at his country estate at Kreisau from 1940 to 1944. They did not seek a violent overthrow of Hitler, but they shared an opposition to the Nazi regime on religious and moral grounds. They believed that the Nazi state would collapse in a few years and saw it as their role to plan for a successor government which would mark a return to Christian and moral principles.

Although this group was not a great threat to Hitler, their belief that the days of the Third Reich were coming to an end was seen by the Nazis as reason enough to view them as traitors. When von Moltke was arrested in January 1944, the Kreisau Circle quickly collapsed.

Source G

These high-minded young men [in the Kreisau Circle] were unbelievably patient. They hated Hitler and all the degradation he had brought on Germany and Europe. But they were not interested in overthrowing him. They thought Germany’s coming defeat would accomplish that. They turned their attention exclusively to the thereafter…Moltke and his friends had the courage to talk — for which they were executed — but not to act.

From The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich by William L. Shirer, 1959

2 Study Source E. Explain in your own words the point which Martin Niemöller is making in this famous passage.

3 Study Source F. Why do you think the German government would commemorate the life of Martin Niemöller on a postage stamp?

4 Explain the meanings of the following terms, as used in this article:

■ propaganda

■ Gleichschaltung

■ paramilitary

■ an underground newspaper

■ sabotage

■ swing music

■ concordat

■ encyclical

5 Study Source G. What does it suggest was the main weakness of the Kreisau Circle?

6 Study Source I. What does it argue were the main effects of the bomb plot of July 1944?

7 Use the internet to find out more about the following opponents of the Nazi regime and produce a classroom display with short biographies of each of them:

a Karl Henrich and Theodor Haubach

b Walter Schmedemann

c Sophie Scholl

d Günter Discher

e Martin Niemöller

f Dietrich Bonhoeffer

g Helmuth von Moltke

h Ludwig Beck

i Claus von Stauffenberg

j Carl Friedrich Goerdeler

The army

The most formidable opposition to Hitler came from the leadership of the German army. Despite its defeat in the First World War, the army, or Wehrmacht, inherited a proud tradition of discipline and military strength. Many of its generals were aristocrats, who looked down on the former Corporal Adolf Hitler and became increasingly alarmed at his reckless plans for expansion, notably the Hossbach Memorandum of 1937.

The chief of the general staff, General Ludwig Beck, warned Hitler to avoid rushing into a premature war and, when his advice was ignored, he sought to persuade his fellow generals to resign en masse to try to persuade Hitler to change his mind. He also secretly contacted the British and French governments, urging them to stand up to Hitler’s demands. Again, in the age of appeasement, his advice was ignored. Although he resigned from the army in August 1938, he remained in touch with other dissident generals and became increasingly involved in plots to overthrow Hitler.

Source I

The effects of [the bomb plot of] 20 July on Hitler’s relations with the Army were not limited to the final destruction of the once powerful position of independence enjoyed by the Army in Germany. Despite the measures taken to ensure loyalty, and despite the purge of the Officer Corps which followed the attempt, Hitler’s distrust of the Army was henceforward unconcealed. This was bound to affect the desperate effort which now had to be made to hold the enemy outside the German frontiers. There was little enough hope of doing that in any case; there was still less when the Commander-in-Chief’s attitude towards his own commanders was governed by invincible suspicion and vindictive spite.

From Hitler: A Study in Tyranny by Alan Bullock, 1962

Operation Valkyrie

By late 1942, defeats at Stalingrad and El Alamein led to increasing alarm among these generals that Hitler was leading Germany to defeat. The Allied invasion of German-occupied France in June 1944 only strengthened this opinion. Beck and a group of like-minded army officers and others, including Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg and the former mayor of Leipzig Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, plotted to assassinate Hitler. This plan was given the codename Operation Valkyrie. After Hitler had been killed, other Nazi leaders were to be arrested and Goerdeler was to be installed as chancellor. He would then save Germany by attempting to negotiate a peace settlement with the Allied powers.

After several aborted attempts to kill Hitler, on 20 July 1944 Stauffenberg placed a briefcase containing a bomb near the Führer during a military conference at his eastern headquarters, the Wolfsschanze (‘Wolf ’s lair’). Although the bomb exploded and four people were killed, Hitler survived with minor injuries and the coup attempt failed. The plotters and many other suspected anti-Nazis were rounded up, some 7,000 in all. Many were summarily tried and executed, including Stauffenberg, Beck and Goerdeler.

Conclusion

Members of all these groups, which in different ways and with varying motives opposed the Nazi regime, deserve to be remembered with respect because of their courage in risking their lives to stand up to a brutal dictatorship. None of them succeeded in bringing it down — that was achieved in 1945 by a combination of military advances by the USSR’s Red Army from the east and the combined forces of the USA and Britain from the west. But they do at least show that not all Germans fell under Hitler’s spell.

Summary

■ Many Germans supported Hitler, but there was significant opposition to the Nazi state:

• political opposition from the remnants of progressive political parties banned in 1933 resistance from young people, such as the

• White Rose group, the Edelweiss Pirates and the Swingjugend defiance from Christian churches and their

• leaders like pastors Niemöller and Bonhoeffer conspiracies within the leadership of the German

• army, culminating in the Stauffenberg bomb plot of July 1944

■ None of these were successful in overthrowing the Nazi regime, though the Stauffenberg plot came close. Yet all deserve to be remembered for their courage in risking their lives to stand up to a brutal dictatorship.