GEOGRAPHICAL SKILLS MAKING THE GRADE

Textual analysis of different source materials

How do geographers approach texts? And what is ‘a text’ anyway?

Textual analysis is a broad term for various research methods used to describe, interpret and understand texts. All kinds of information can be obtained from a text — from its literal meaning to the subtext, symbolism, assumptions and values it reveals.

The methods and techniques used to conduct textual analysis depend on the type of text, as well as the broader aims of the research. Researchers often try to connect the text to a wider social, political, cultural, economic or even environmental context, and this can prove fruitful.

An important point to note is that underlying this type of analysis is the idea that what is written about the world does not simply describe a fixed reality but also helps to shape that reality (as people’s opinions and actions are shaped by what they read, see or hear). Textual analysis therefore helps us to understand a place but also the processes which shape and reshape it over time. In recent years, textual studies have played an important part in the recognition that representations and images dominate our culture and therefore have a central place in geography.

You might be surprised to learn that this ‘armchair research’ can also be potentially relevant to A-level geography. Our experiences of geographical methods, especially fieldwork, are often focused on being ‘in the field’, without any discussion of what we mean by this concept. The pandemic has perhaps given us an opportunity to reflect on how we can learn from diverse data. In some instances, this gives us opportunities to read about local or regional geographic contexts as part of the investigative process.

What is ‘text’?

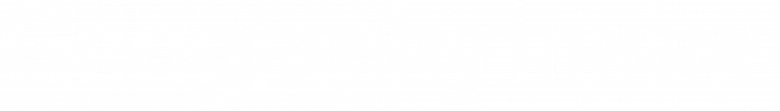

The term ‘text’ is perhaps broader than it initially seems. A text can be a piece of writing, such as a book, an e-mail, an article, a social media post or more formally transcribed conversation or interview. But a text can also be any object whose meaning and significance you want to interpret in depth: a film, a piece of music, an image, an artefact, even a map. Table 1 provides an overview of different types of text.

Analysis of texts

The methods you use to analyse a text will vary according to the type of text/object and the purpose of your analysis. The analysis of a short story about a place, for example, might focus on the imagery, narrative perspective and structure of the text, whereas for a film it’s not only the dialogue but also the cinematography and use of sound that could be relevant to the analysis.

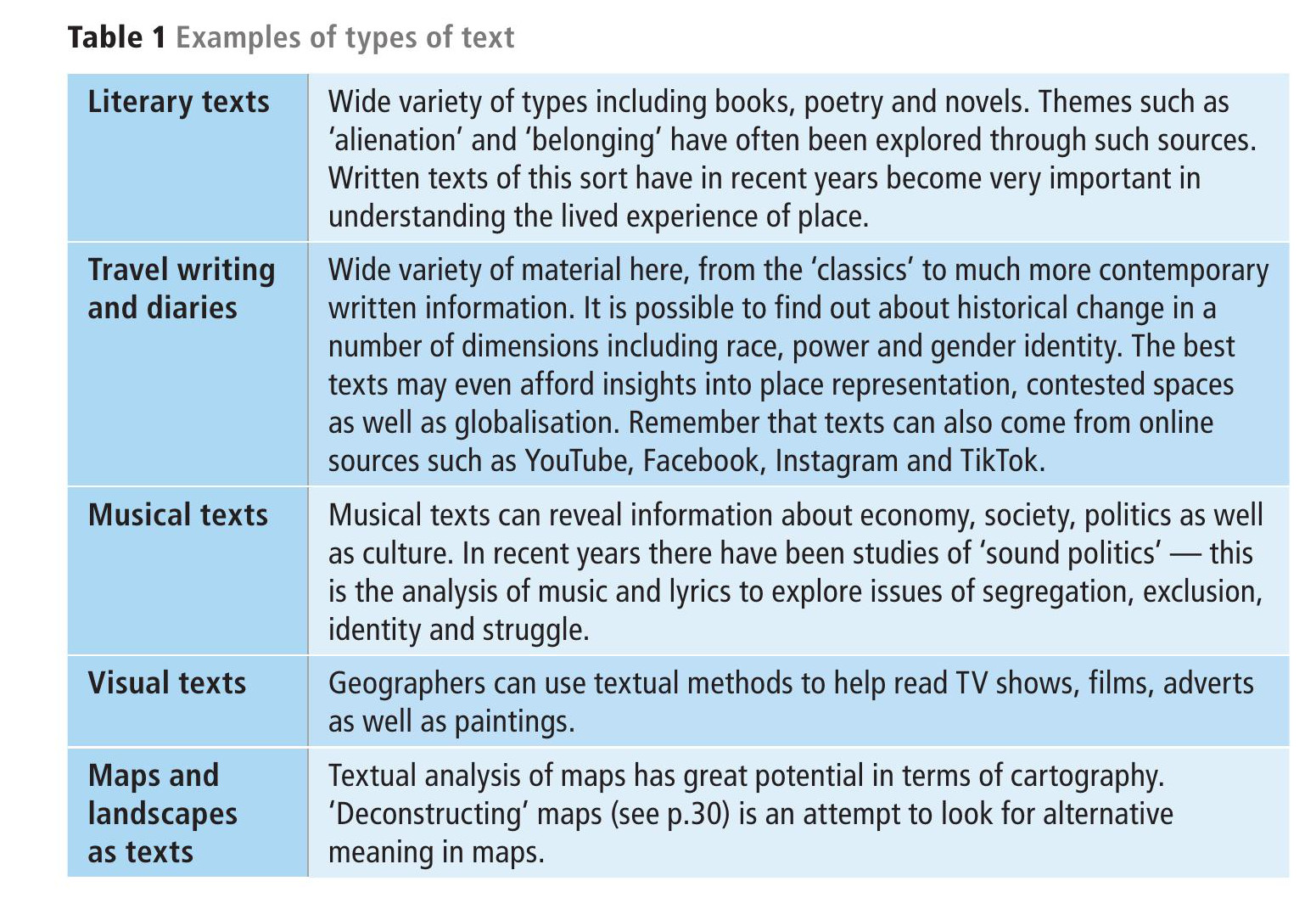

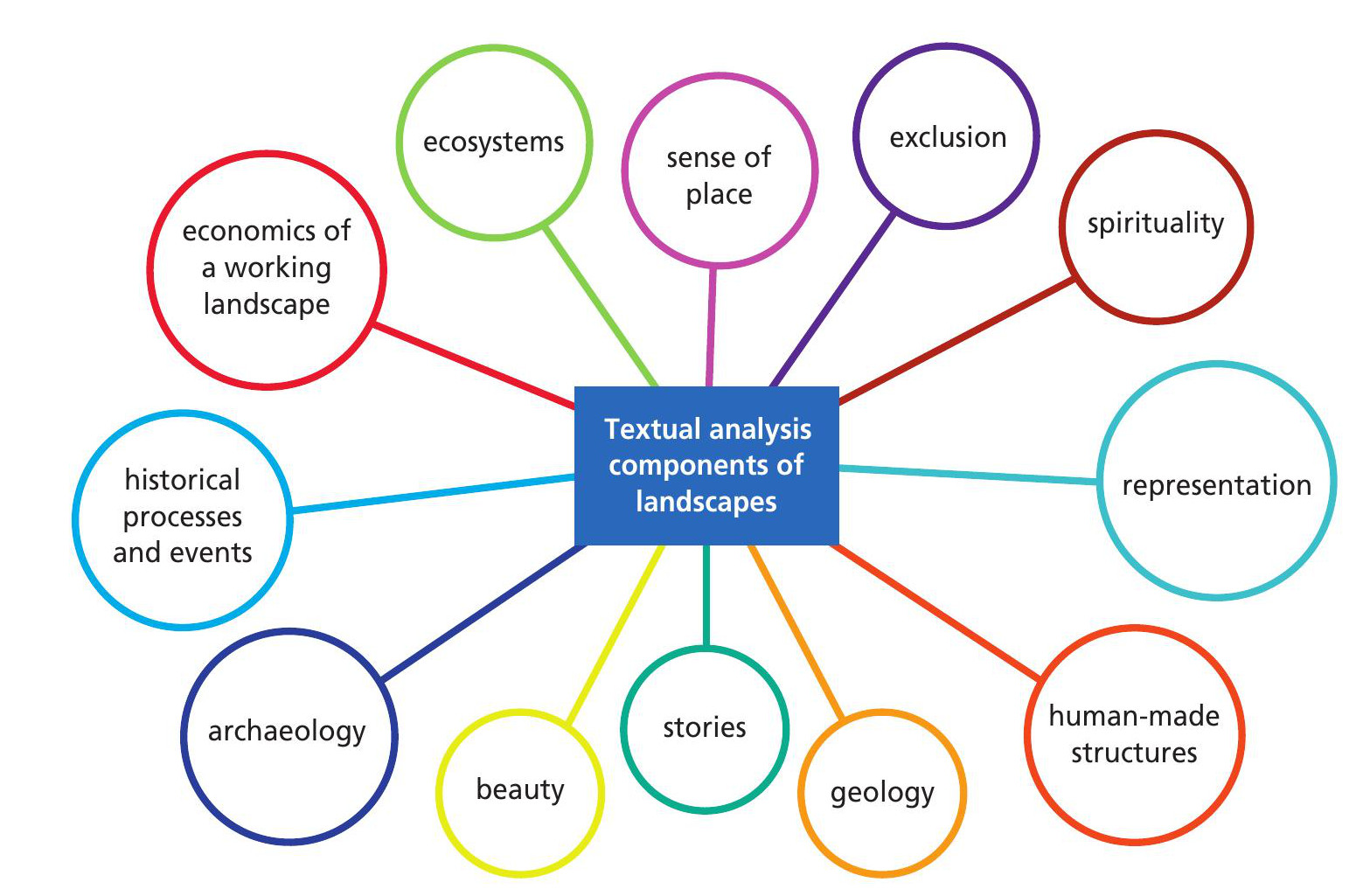

Making sense of texts and textual metaphors requires a process of ‘opening up’. It’s far from straightforward or easy to explain, but the suggestions in Figure 1 might be useful to help navigate a thought process. Ultimately you will need to build confidence in various approaches and techniques of textual analysis, and of course look at different methods to find a way that works well for your investigation.

Textual analysis can take many forms:

■ A building might be analysed in terms of its architectural features and how it is used and navigated by visitors.

■ You could analyse the rules of a game and what kind of behaviour they are designed to encourage in players.

■ A picture of landscape can be read through what time the image was taken, as well as which aspects of landscape have the most focus (or are not actually photographed).

Content analysis

Geographers might use content analysis to find out about the purposes, messages and impacts of communication of particular content. We can also make judgements about the context of the authors and intended audience of the texts. These ideas are central to textual analysis.

In one respect, content analysis can be seen as a quantitative analysis tool — measuring the numbers/occurrence of certain words, subjects, phases or even concepts. Here’s an example:

‘To find out about the strength of local conflict in respect to new planning proposals for a large new housing development in an area, you could analyse the frequency of terms such as ‘school’, ‘view’, ‘parking’, skyline’, etc. and then use statistical analysis to find patterns. ’

In addition, content analysis can be used to make qualitative interpretations by analysing the meaning and possible relationship of words and concepts:

‘To gain a more qualitative understanding of employment issues in a local community, you could locate the word ‘unemployment’ in blogs/ tweets/Instagram etc., identify what other words or phrases appear next to it (such as ‘economy’, ‘inequality’, ‘living-wage’, or ‘low-pay’), and analyse the meanings of these relationships to better understand the intentions and targets of different types of media or individuals. ’

Specifically, you should think about how content analysis might help you in terms of a geographical investigation. The list below provides points of focus, although many are in fact interlinked with each other:

■ Understanding the intentions (narrative) of an individual, group, stakeholders or institutions linked to the texts they have produced.

■ Identifying misinformation and bias in communication materials.

■ Revealing differences in styles of communication in different contexts and to different people (or in different communities).

■ Finding correlations and patterns in how concepts are communicated through different texts.

■ Analysing the consequences of communication content, such as the flow of information or audience responses.

Using spreadsheets for textual analysis

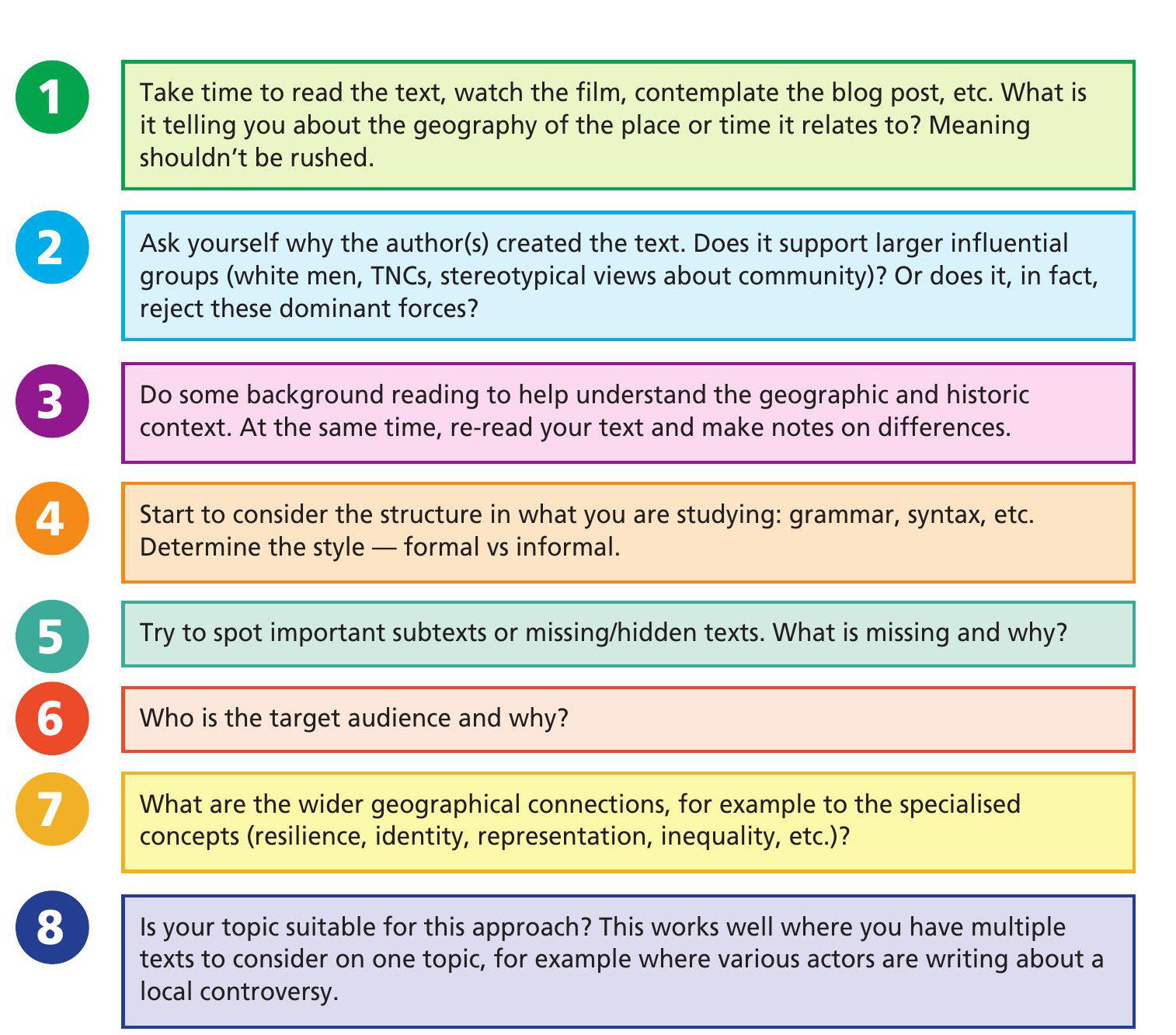

In the past, GEOGRAPHY REVIEW has produced guidance around sentiment scoring (see GEOGRAPHY REVIEW, Vol. 32, No. 3). Spreadsheets such as Excel can be used to perform more quantitative textual analysis. In Figure 2, for example, the Azure Machine Learning Plugin for Excel has been used to analyse some responses from an online questionnaire survey. It is, in fact, relatively simple to do.

First, the qualitative responses text was converted to a table, then the plugin was used to calculate both a sentiment statement (positive, neutral, negative) and a corresponding score between 0 and 1. The highest numbers were positive in sentiment and lowest numbers provided a negative sentiment. Finally, conditional formatting was used to colourcode the score with red for negative grading to dark green for very positive.

Of course, there are many other ways that spreadsheets can be used as a tool of textual analysis. For example, there are various online sources which will convert tables of text into a word-cloud. Figure 3 shows the same data from the online swimming pool questionnaire used to generate a word-cloud using www.worditout.com.

‘Deconstructing a map’ and landscape as text

Maps are often very selective and generalised. They include what the mapmaker (cartographer) sees as important, but we also need to consider what the cartographer has decided not to include. Maps often influence the way we view and understand the world, and can create and maintain particular discussions about the world and international relations, with very real implications for those in the territory they represent.

We can approach the deconstruction of maps from three important angles:

1 First, we can look to see how maps can show change over time.

2 Second, we can look at different maps and see which pieces of information are included and which are not, and how this might be influenced by particular mapmakers.

3 Third (and linked to the second idea), we can consider maps as pieces of misinformation or even propaganda (intentionally or not).

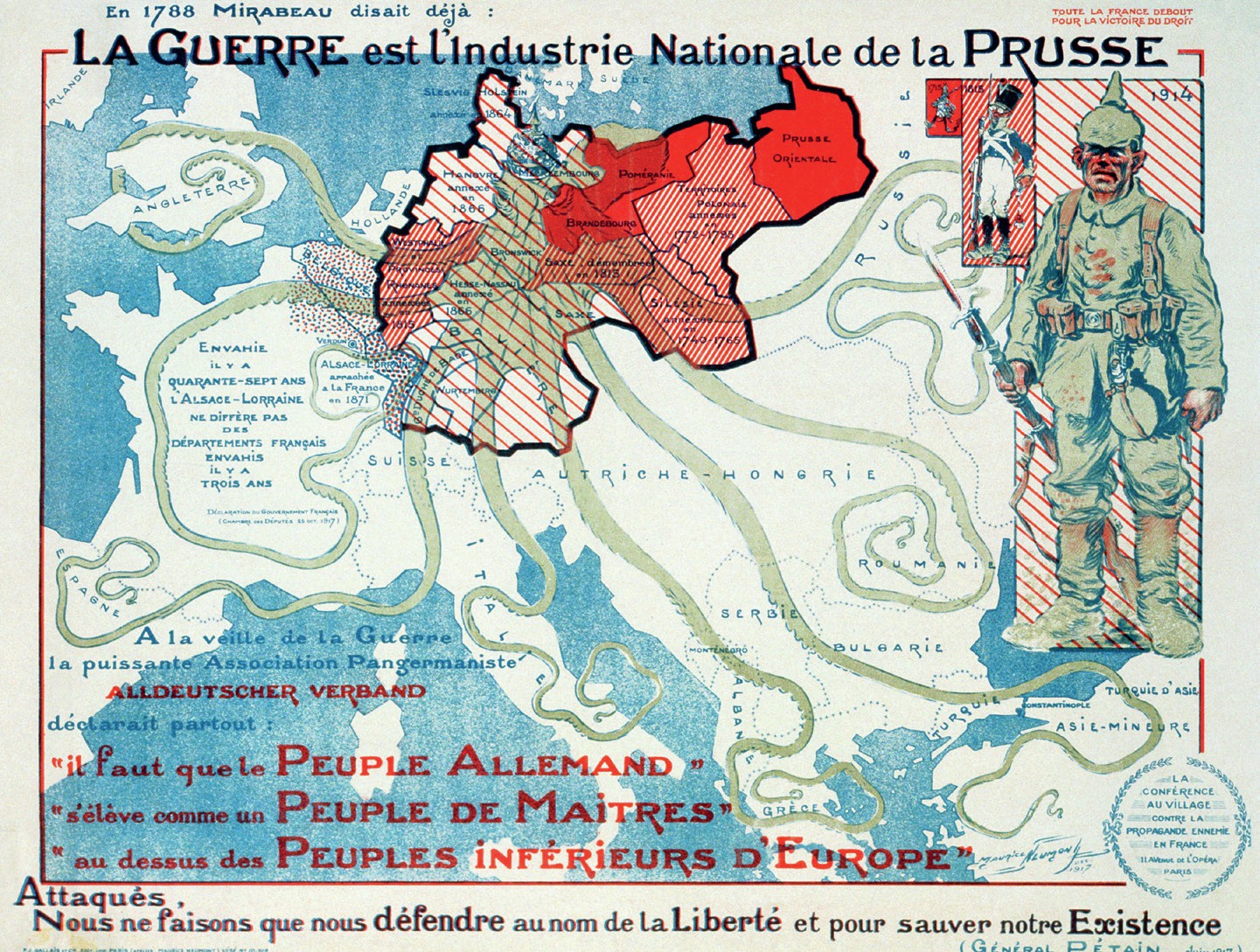

In point 3, for example, political influence often concerns territorial claims, nationalities, national pride, borders, strategic positions as well as spheres of influence and regional inequality (see Figure 4). The goal of ‘cartographic propaganda’ is to shape the map’s message by highlighting supporting features while concealing conflicting information.

In terms of using textual analysis of maps for an NEA, then, it may be far more likely that local historic maps will play a role in understanding local places. The National Library of Scotland, for example, has an excellent set of online historic maps that can be used side by side (see Resources).

Geographers sometimes talk about ‘reading a landscape’. Images of landscapes reflect the intent of the author and so the ideas of textual analysis can be applied to thinking about what these authors are saying about landscape and what that tells us about the relation between people and the landscape.

You might want to consider some of the elements in Figure 5 and annotate images of landscapes to indicate how you are interpreting them. Why not colour-code annotation elements based on physical or human geographies, for example?

Conclusion

Textual analysis is not an easy option. It may appear easier than getting wet in the field, but it requires structure and discipline to be meaningful. Textual analysis is an important way of ‘doing geography’, particularly in the context of human geography work on changing places, and therefore is a useful method to consider as you plan your NEA research.

Texts are always unavoidably political, biased and personal. That’s what makes them interesting as well as challenging to use and interpret. As a geographical researcher, you must navigate their peculiarities, lack of impartiality and complexities to take away new meanings and contexts. Textual analysis almost always involves some level of subjective interpretation, which can affect the reliability and validity of the results and conclusions.

That should always be acknowledged and written down.

Are you up for the challenge?

RESOURCES

How to detect the distortions of maps: www.tinyurl.com/2ttjz3mk.

Reflections on J. B. Harley’s ‘Deconstructing the Map’ (Krygier 2015): www.tinyurl.com/bda7uv24.

Wikipedia entry on cartographic propaganda: www.tinyurl.com/4dnfwnhe.

Video instructions for sentiment analysis using Excel: www.tinyurl.com/3ad9sex3.

Instructions for content analysis: www.tinyurl.com/yd9pa5b8.

National Library of Scotland online maps: www.tinyurl.com/34y3jd25. In particular, see the ‘Side by side viewer’.