Deglobalisation

Effects on business

Robert Nutter examines the effects of deglobalisation on the business world in recent years

EXAM LINKS

This case study is relevant to the following topics in the AQA, Edexcel, OCR and WJEC/Eduqas A-level specifications:

■ global business

■ globalisation

■ global industries and companies (multinational corporations)

■ PESTLE

■ managing change

■ causes and effect of change

■ business objectives and corporate strategy

■ trade blocs

Globalisation is not new — it has been in existence for centuries — but it has come in different cycles. One phase in the nineteenth century saw the emergence of new sources of raw materials and markets, with the industrial revolution providing the manufacturing processes and transport and communication links to exploit them.

According to Harvard Business School, ‘globalisation is the increase in the flow of goods, services, capital, people, and ideas across international boundaries.’ Other descriptions of globalisation include the ‘death of distance’ and the increased economic interdependence of nations. ‘We live in an age of globalization’, according to Forest Reinhardt, Harvard Business School professor, who teaches the global business course. ‘That is, national economies are ever more tightly connected with one another than ever before.’

The above paragraph has until relatively recently described the accepted future direction of the global economy. The latest phase of globalisation, which started in the 1990s, has its origins in a number of factors, including the creation of the internet and the falling costs of travel, telephone calls and containerisation, as well as the global relaxation of capital and migration controls. The end of communism in central and eastern Europe following the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the emergence of China as an economic powerhouse increased the area of the globe open to trade, supported by the widening of the Suez and Panama canals, which allowed larger ships to travel through them.

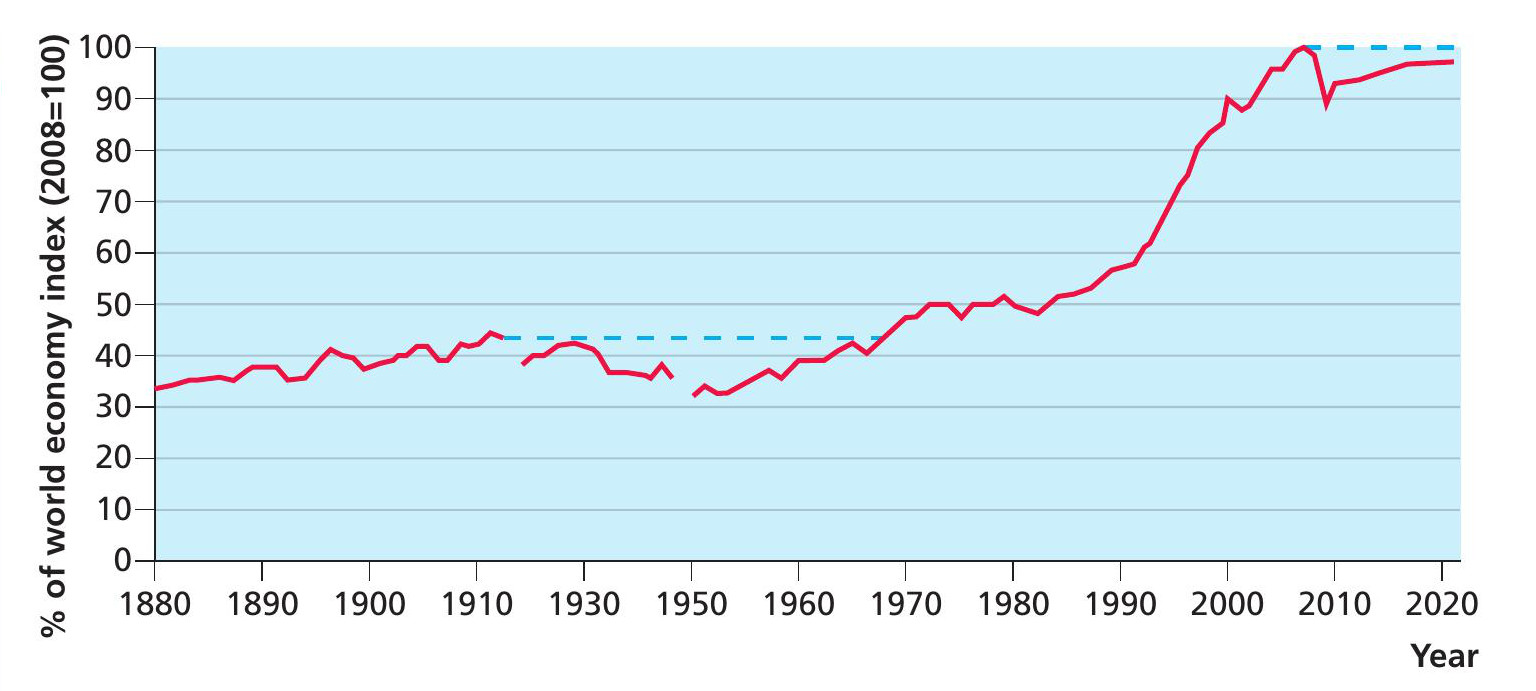

Figure 1 shows the period between the early 1990s and the financial crisis in 2008 as the ‘golden’ period of the most recent period of globalisation, with the growth in world trade continually exceeding the growth of world GDP. Commenting on the period between 1997 and 2007, the former governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, called it the ‘NICE decade’ — Non-Inflationary Continuous Expansion. Cheap imports from low-wage economies kept inflationary pressures down and allowed economic growth and standards of living to rise.

Seismic shifts

The global economic landscape, however, changed with the financial crisis in 2008, Brexit in 2016, Covid-19 in 2020–2021 and the Ukraine crisis in 2022. These events have threatened the process of globalisation, with interdependence and long supply chains no longer seen as cheap and convenient for business. Another threat to globalisation has been the rise of populism — apolitical approach that tries to appeal to ordinary people who feel that their concerns are disregarded by established elite groups (such as the educated middle class).

Populists are often anti-globalisation, as they seek to appeal to those workers who believe that their job security and living standards have been threatened by cheap imports from emerging economies. Donald Trump’s ‘America First’ policy included protectionist policies in the form of tariffs, in particular against China and the EU. Marine Le Pen in France and Nigel Farage in the UK would also be seen as part of the populist movement.

The Covid-19 pandemic reduced the movement of labour globally. For the UK in particular, as a result of Brexit, there was the end of frictionless trade with the EU. Disputes between the West and China over security, technology (intellectual property) and human rights have also slowed the process of globalisation.

In the 2020s, the talk is of deglobalisation or maybe ‘slowbalisation’, where there is a fall in the growth of interconnectivity. Some believe that the recent globalisation model is unsustainable, because it leads to financial crises, accelerates climate change, increases inequality and makes pandemics more likely (Professor Ian Goldin of Oxford University). The French president, Emmanual Macron, has declared that ‘this kind of globalisation was reaching the end of its cycle.’

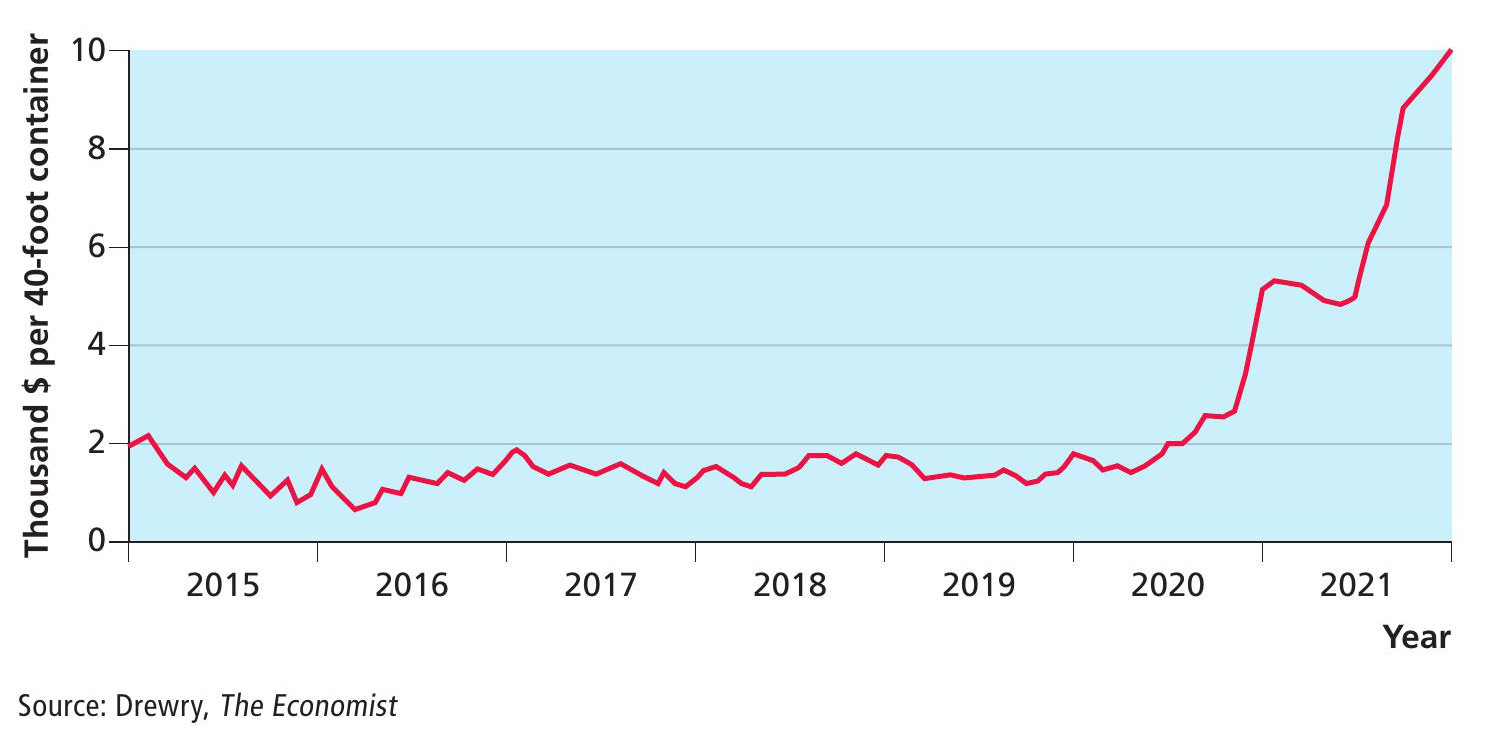

The Covid-19 pandemic dramatically demonstrated the vulnerabilities in long supply chains. When the world opened up in 2021, transportation costs soared because ships and containers were in the wrong place (Figure 2). Pandemic restrictions have intensified supply shortages and the war in Ukraine has threatened food and energy security. The Ukraine war has increased global tensions and could mean a permanent change in patterns of trade, as Russia finds different trading partners as a result of economic sanctions. Adam Posen of the Peterson Institute for International Economics has suggested that there could be a world economy split into blocs, ‘each attempting to insulate itself from and then diminish the influence of the other.’ The USA and EU versus Russia and China seems a possible scenario.

Global adaptation

How has the business world adapted to the seismic shifts in the global economy that have occurred in recent years?

The main issue has been the long and complex supply chains developed in recent years, based on cost minimisation and a just-in-time approach to business activities. Nowhere has the Western world’s reliance on suppliers from east Asia been more exposed than in the critical shortage of computer chips, which are used in a variety of products, ranging from fridges and ovens to cars and video games. This has led to car manufacturers having to shut down production, resulting in a surge in the price of second-hand cars. In ‘normal’ years, Europe’s car manufacturers did not stockpile enough chips from suppliers in Asia, particularly Taiwan.

The EU has recently supported a £125-billion plan to boost chip-making in Europe and President Biden has called for production to start in the USA. Raphael Bostic, president of the Atlanta Federal Bank, recently said that the pandemic and the Ukraine crisis have seen businesses ‘reorienting production and supply networks away from pure cost minimization and more towards resilience and risk tolerance.’ Business leaders have been prompted ‘to start diversifying supplier locations and firms, increasing inventories, and bringing production closer to final markets to maximise reliability. Think of it as a shift to just-in-case inventories from just-in-time’.

In a similar vein, the Guardian said (11 March 2022) that ‘the pandemic dramatically demonstrated the vulnerabilities in long supply chains and made countries look closer to home. Narendra Modi [the Prime Minister of India] has announced a Self-reliant India scheme; Japan has introduced incentives for companies to onshore production.’ Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital has said that the recognition of the negative aspects of globalisation ‘has now caused the pendulum to swing back toward local sourcing. Rather than the cheapest, easiest and greenest sources, there’ll probably be more of a premium put on the safest and surest’.

UK businesses

In an article entitled ‘De-globalization is ripping up the global trade order’, the Sunday Times (27 March 2022) identified several examples of UK businesses benefitting from the reshaping of the global economic order. PP Control and Automation, a Midlands firm, builds control systems for large machinery manufacturers. Tony Hague, the chief executive, is quoted as saying that his customers can now see the hidden costs of using the cheapest suppliers in Asia, explaining that ‘it might well be that we, a UK supplier, are 10% more expensive than a Chinese supplier, but when you start factoring in all the other elements, then all of a sudden the UK supplier looks very attractive’.

Similarly, David Nieper, which sells high-quality women’s clothing, has spent £4.5 million on a UK-based factory that can dye and cut fabric. The firm is also planning to import raw cotton to be woven into fabric. Christopher Nieper, who runs the family business, said that ‘it always seems to be much cheaper to get finished products from overseas. But in fact, you’re faced with not just the lead time but minimum sized orders’.

Boohoo

Retailer Boohoo has recently opened a new factory in Leicester, meaning that its acquired brands Debenhams, Dorothy Perkins and Wallis will be making clothing in the UK again after moving offshore almost three decades ago. The new factory produces 6,000 garments a week and will reach 20,000 when a second shift is introduced. Boohoo says that the big advantage of manufacturing clothing in the UK is speed, with the ability to produce items in only two weeks from design and one week on a repeated order. This compares to a six-month lead time that high street brands typically have with overseas suppliers. John Lyttle, Boohoo’s Chief Executive, said:

‘we are going to be making clothes in Britain and 40% of them are to be sold internationally so we’ll be exporting again. I think we’ll see more companies shift to UK and European manufacturing. Everything we have seen over the past two years has heightened the importance of being closer to home. Shipping delays have improved but container prices are still very high.’

However, Boohoo still sources half its clothes from Asia, and other mass market clothing retailers have been much slower to start reshoring. For example, Next and Primark have increased sourcing of clothing from Turkey rather than east Asia, but only on a small scale.’

In January 2021, British bus-maker Alexander Dennis (ADL) announced it will manufacture the chassis for its electric buses in the UK. Previously, the chassis were made in parent company BYD’s factories in Hungary and China and shipped to the UK for assembly. This move has taken place despite Hungary and China having lower production costs than the UK, and it will ensure that complete vehicles will be made in Britain. According to Production Engineering Solutions (12 February 2021), this:

‘is the latest strong example of “reshoring”, or companies moving production of a key component to the UK from abroad or, in some cases, relocating whole factories to the UK. The reshoring trend, which was established long before the coronavirus pandemic, has several logical reasons behind it, but the two most important today are probably Brexit and COVID- 19 and the supply chain disruption that both cause.’

The effects of Brexit

The UK’s position in the deglobalised world has the added effect of Brexit, which finally came about in January 2021. DW (Deutsche Welle), Germany’s international broadcaster, reported (2 June 2021) how Brexit was affecting British exporters: ‘Brexit is proving far from profitable for many UK small- and mediumsized enterprises (SMEs). Swamped by paperwork, taxes, and eye-watering additional costs, some are having to shutter their EU operations indefinitely. Others, unwilling to cut off European customers, are simply upping sticks, and moving to the Continent.’ A Scottish dog chew manufacturer, Antos Pet Foods, which saw its sales to Europe drop ‘off a cliff’ after Brexit, has been forced to open a production facility in France to cater for its European customers.

When the UK left the EU, the government secured a tariff-free trade deal with Brussels, the Trade and Co-operation Agreement, but massive non-tariff barriers have emerged since the start of 2021. James Sibley, head of international affairs at the FSB (Federation of Small Businesses), has said that ‘with the changes to VAT, rules of origin, customs paperwork, these are related to the UK leaving the customs union and single market, and us undergoing such a huge change to our trading relationship with the EU. These changes are not going away.’

Looking ahead

Globalisation may just stall over the next decade, but a period of deglobalisation — with cross-border flows of trade and capital falling as a share of GDP — is increasingly likely, given the deterioration of relations with Russia and growing international tensions as the Ukraine war costs more lives. There are growing bilateral tensions between Russia and the West, and also with China, an autocratic superpower, which is now viewed with increased suspicion and as a strategic threat to the USA. Nonetheless, 300 of the world’s top 500 businesses have facilities in Wuhan, China.

Low wage costs are the driver of globalisation. However, as production techniques become more capitalintensive, low wage costs are less important for business.

As Figure 3 shows, the first wave of globalisation ended in a period of deglobalisation, while the second wave was followed by a period of ‘stasis’ — no real change. Are we now at the end of the third wave, and if so, will we see globalisation stall or actually be rolled back? According to Neil Shearing of Capital Economics (7 October 2019), ‘globalisation has undermined the power of national governments and been blamed for rising inequality, multinational tax avoidance and unwanted migration.’

Clearly there is much uncertainty in the world, and business is likely to think more conservatively in its decision-making in the short term. Alternatively, in the long term, will globalisation march forward, embracing Africa as the new Asia?

PRACTICE EXAM QUESTION

Assess the impact on aircraft manufacturer Airbus of the UK leaving the European Union. (12 marks, Edexcel)

BusinessReviewExtras

Check your answers at www.hoddereducation.co.uk/businessreviewextras