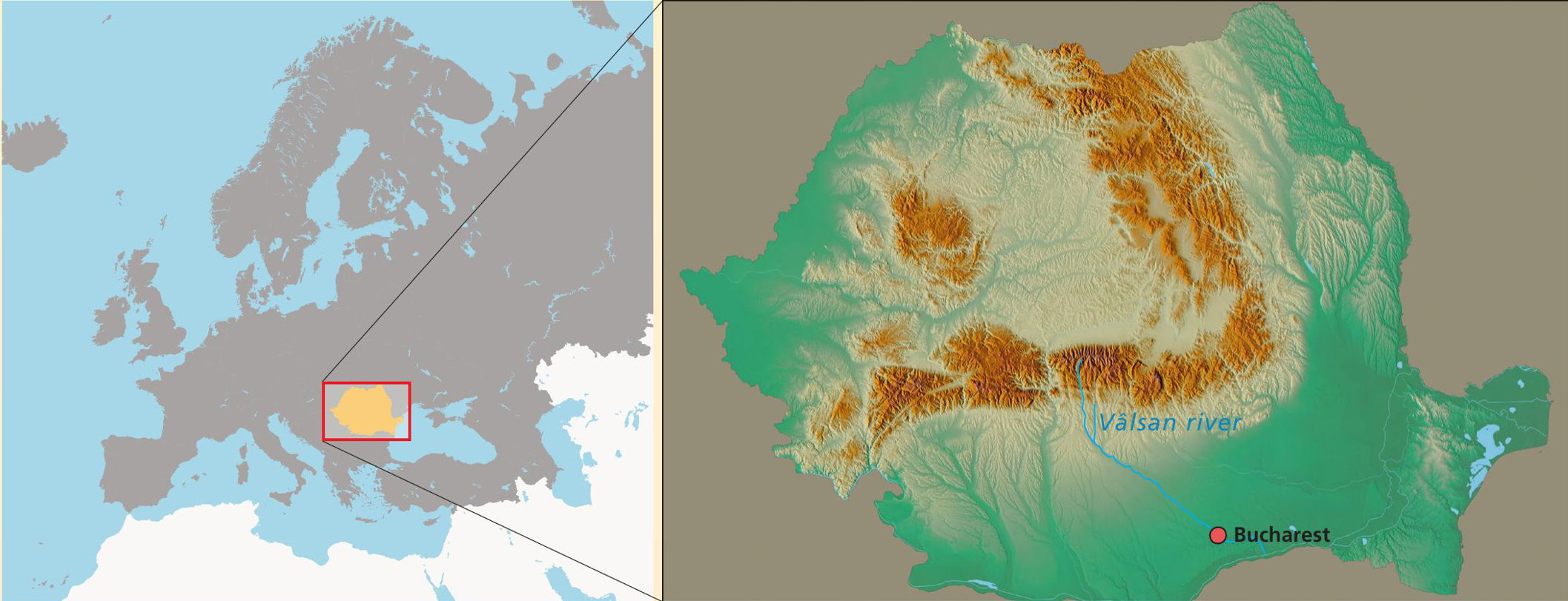

Around 150 kilometres northwest of the Romanian capital Bucharest lie the Făgăraş mountains of the Southern Carpathians. Importantly, it is here where the Vâlsan river begins (see Figure 1) – the last refuge of one of the world’s rarest fish, the asprete (Romanichthys valsanicola). Relatives of the asprete have swum in these waters for more than 65 million years. However, because of human activity over the last 60 years, this fish will become extinct unless we actively intervene now.

The asprete is commonly known as the Romanian darter. Despite the name, it is more closely related to the European perch than it is to darters. DNA sequence analysis suggests that the asprete and perch diverged from their most recent common ancestor around 25 million years ago (mya). This coincided with tectonic plate movements in southern Europe around 30–25 mya, which separated the asprete from its European relatives. Asprete, like perch and over 50% of all vertebrate species, are ray-finned fish (see Figure 2). They are distinguishable from perch by a number of adaptations – for example, they are small, around 110 mm long at maturity, have a rather flattened body shape, no swim bladder, nasal flaps, reduced dentition and an incomplete lateral line (see Box 1). Asprete habitats are fast-flowing, shallow mountain streams with gravel beds. Unusually for a freshwater species, the asprete is nocturnal, hiding by day under rocks. It feeds on fish and insect larvae, and in turn is predated by trout.

Your organisation does not have access to this article.

Sign up today to give your students the edge they need to achieve their best grades with subject expertise

Subscribe