PROSPECTS

From tigers to TV

Megan McCubbin is a zoologist, photographer and wildlife presenter. She spoke to BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES REVIEW about her work, and the route that led her there

BSR Did you think that animal biology would be something that would shape your career, rather than remain simply an interest?

MM Oh yes – before I even started my degree I knew it was going to be my life. In my bedroom when I was growing up I had hissing cockroaches, snakes and praying mantises. I did have hamsters, poodles and more conventional companions, but I particularly enjoyed unusual animals.

I was incredibly lucky to get to know four tigers when I was 12 years old. They lived in what is now known as the Wildheart Trust, on the Isle of Wight. It’s a sanctuary for ex-pet-trade animals, and these four tigers, which had been destined for life in a circus, had been rescued and hand reared. I developed an incredibly strong relationship with them – I was there every weekend and every summer, grabbing every opportunity to interact with them, and became very fond of them. I felt like I was going through my teenage years along with them. They are probably what drove me to make a change from performing arts to science, because I felt a responsibility on their behalf, to fight tooth and nail for their welfare, and their wild counterparts, and to help protect other animals that had been enslaved in the service industry or illegal wildlife industry. So they really changed everything for me.

BSR So you also considered the performing arts?

MM Yes. I was even hoping to go to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London (but would never have got in). I found science at GCSE very difficult, and around Year 9 I didn’t think science was for me. I am dyslexic, so I struggled to learn conventionally taught science. I ended up going down the performing arts route – little did I know that it would be quite handy for me in my career.

Just after I chose my GCSE subjects, I realised that I’d made a massive mistake. I found that I could do science if I really pushed myself. I had to go into the classroom to get the information and then take it away and relearn it in the way that suited me, because I did not fit into conventional classes very well (and I was terrible at exams).

I went to Peter Symonds College in Winchester, where they were very gracious and understanding, and allowed me to do A-level environmental science. Then I did a foundation year of biological sciences at Carmel College and a degree in zoology at the University of Liverpool.

BSR You did your first media presentation while still at university – aBBC3 Undercover Tourist episode on the bear bile industry – how did that come about?

MM I had lived in China for 4 months over the summer at the end of my university first year, working for a charity called the Animals Asia Foundation. It is the most incredible charity. It rescues bears, typically Asiatic black bears, but also some Tibetan brown bears and sun bears, from bear bile farming. Animals Asia has two amazing sanctuaries set up for bears, where it treats and rehabilitates bears that have been rescued from the industry, as sadly they can never be returned to the wild. The bears are given a large enclosure, a varied diet and different types of enrichment.

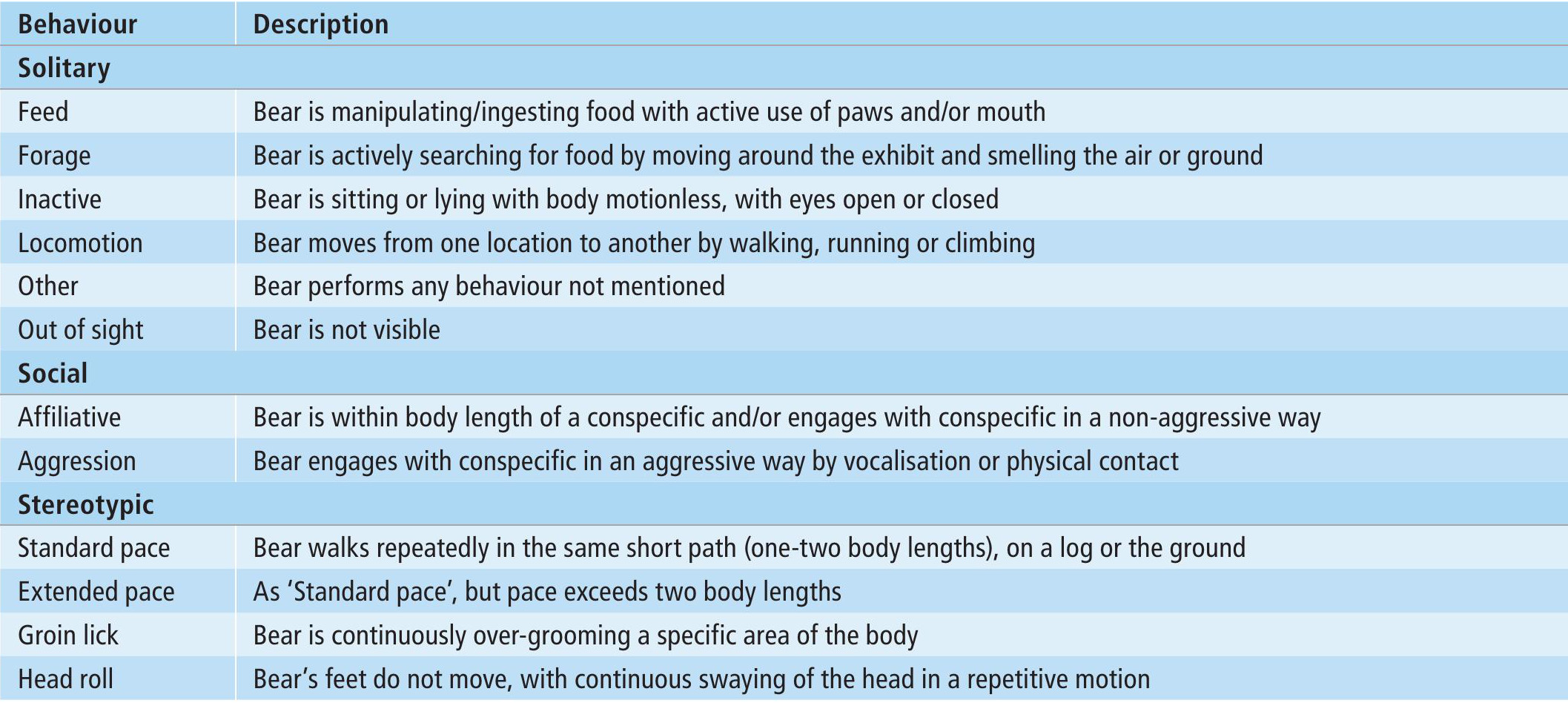

My job was to spend the mornings making cocktails of medications for the special-care bears. I was a behavioural specialist volunteer, so I was allocated a group of bears to monitor in the afternoons using behavioural ethograms (see Box 1). We had a female bear called Bonnie – she had been there since she was a cub. She had always been quite sassy, and told other bears off if they approached her favourite male, Prince. But her behaviour had changed. My job was to analyse the behaviour of the bears in this particular group, which turned out to reflect the fact that they had been moved to an area with fewer trees (less cover). However, Bonnie and the group eventually settled well in the new enclosure.

Box 1 Example behavioural ethogram for captive bears

An Undercover Tourist episode had fallen through, and the BBC was looking for something at short notice. As I’d had that experience with bears, and had a few friends who worked in the BBC, I was asked to step in to cover bear bile farming (which is illegal in Vietnam). So just a couple of days after returning from my second-year university field course in Uganda, I went to Vietnam for 10 days to film a 10-minute episode. We didn’t need to be undercover for some of this as you could walk straight into the farms off the street, but we did use hidden cameras in shops selling the products. We also found bears in people’s garages and in their kitchens, often in tiny cages in the most dire conditions. Despite the harrowing situation, we were able to highlight the work of Animals Asia, which works with governments to end the practice.

BSR What would be your advice to readers aspiring to a career in media?

MM You really need to get practical experience as well as working hard on your studies. While I was at school, my weekends and summers were spent at the wildlife sanctuary or volunteering at the local wildlife hospital. Every summer at university I took up an internship somewhere to get more hands-on experience. Because I loved it so much, I did two internships at Bimini Biological Field Station in the Bahamas – also known as Shark Lab. I was researching predatory ecology and behaviour, and trying to understand how big predators shape their environment. Every time I got in the water with a shark, the hairs on the back of my neck would stand up – I was incredibly excited to share space with an animal I respected and loved.

BSR What have you enjoyed most about TV presenting?

MM I love challenging people’s concepts about animals that don’t always have the best reputations. I loved doing films on rats, slugs and jellyfish for Winterwatch a couple of years ago. I sat in a garden watching a family of rats for a couple of hours, and it was so fascinating I forgot the camera crew was there. I got to swim with jellyfish in freezing cold water. There are two words that I hate more than any others in the English language – I call them the p-word and the v-word. I never use the terms p*st or v*rmin, because all organisms have their niche and deserve some love.

The best part of my job is that I get to speak to people who know a specific area really well. I get baseline knowledge from those who have dedicated their lives to conservation and I get to spend time just picking their brains, which is really exciting, and then get the chance to communicate that information to a big audience.

BSR What do you find most frustrating?

MM The lack of progress. I spend my day reading publications and trying to talk to people about issues – to get them to change their minds or their behaviour – but they so often dig their heels in. When I see the rate of biodiversity decline, global temperatures rising, flooding and people starving, alarm bells are ringing in my head.

I’ve been really lucky to go around the world from a really young age, and I’m incredibly aware of what a privilege that has been. I’ve seen some amazing communities and cultures, but having had that experience, my eyes are very much open to the struggles that many of those communities are facing, and I’ve seen massive changes. As a 15-yearold, I stood on a glacier – and now that glacier is no longer there. We see negative statistics every day, but you have to focus on the positive and use your energy as a motivator for change. I try to present the incredible things I know to the politicians and the CEOs to persuade them to lead the way, so that everyday consumers can make the right choices. For example, when we go into farm shops or our supermarkets, organic food is so much more expensive than foods that come from factory farms, so we need some systematic action.

BSR You are a very competent photographer yourself, winning your first award – Young Photographer of the Year – when only 12. To what extent do you rely on the team, and how much do you drive the content of what you do on TV?

MM It’s 100% a team effort. I’m incredibly lucky to be surrounded by some of the most talented, knowledgeable, multiskilled people, who can drop everything and help when things start to go wrong on live TV (as they inevitably do). Everyone has their own niche – what they’re good at – and the researchers are pretty much working all year round. When the team comes together, and we throw around all kinds of crazy ideas, it can be the most creative and inspiring forum to be sat in. It really is an open invitation for anyone to put in suggestions, which is something that I find exciting and quite unique about this industry. The film makers are already out filming the pre-recorded material for the next episodes of the Watches – so please tune in.

TERMS EXPLAINED

Bear bile farming ‘Farming’ live bears in order to extract bile from their gall bladders for use in commercial products. See https://tinyurl.com/2p926s2f

Behavioural ethogram A catalogue or inventory of behaviours or actions exhibited by an animal.

RESOURCES

Packham, C. and McCubbin, M. (2021) Back to nature. How to love life – and save it, John Murray Press.

BBC programmes and more on wildlife: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b007qgm3

Animals Asia: https://www.animalsasia.org; ‘Behind the scenes at the bear sanctuary’ https://tinyurl.com/AA-bear-sanctuary; why not volunteer? https://tinyurl.com/AA-volunteer

Bimini Biological Field Station Foundation: https://www.biminisharklab.com; why not do an internship? https://www.biminisharklab.com/volunteer

Wildheart Animal Sanctuary: https://tinyurl.com/Wildheart-A-S