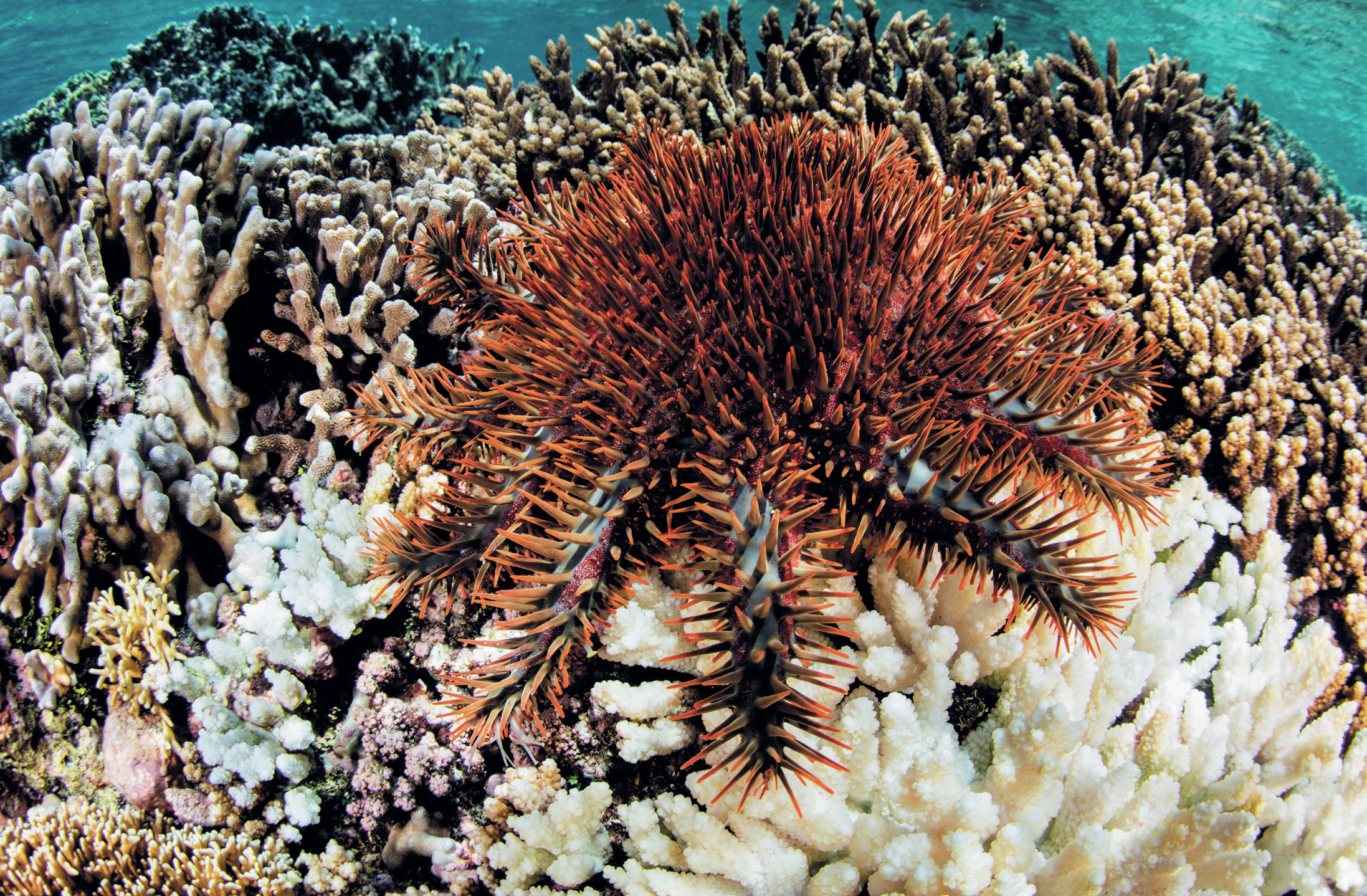

Coral reefs around the world face many challenges. Coral bleaching (linked to climate change), pollution and hurricanes all take their toll. Many reef systems in the Indo-Pacific region, including Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, face an additional, biological threat. Each adult crown of thorns sea star – COTS – can consume its own body area of living coral every night (see Figure A). These nocturnal animals can grow to a width of up to a metre, and on average each individual destroys 13 square metres of coral per year.

In an ecosystem in balance, these coral predators would pose little problem, but humans have overfished their predators (see Box 1) and agricultural runoff has provided rich nutrients for their larvae. Booming numbers of COTS have become the major cause of coral death for the already-struggling Great Barrier Reef and recent research has revealed a sinister twist to the story. While corals can recover, it takes time for them to establish – but the COTS can wait. The juvenile stage of COTS is herbivorous. Normally, the juveniles switch from eating algae to consuming coral when around 4 months old. But if coral is not plentiful, the juveniles can survive on algae until they are up to 6.5 years old, and then switch to eating coral – thwarting coral recovery.

Your organisation does not have access to this article.

Sign up today to give your students the edge they need to achieve their best grades with subject expertise

Subscribe